Illustrating Reinforcement Learning from Human Feedback (RLHF)

This article is also available in Chinese 简体中文.

This article has been translated to Chinese 简体中文 and Vietnamese đọc tiếng việt.

Language models have shown impressive capabilities in the past few years by generating diverse and compelling text from human input prompts. However, what makes a "good" text is inherently hard to define as it is subjective and context dependent. There are many applications such as writing stories where you want creativity, pieces of informative text which should be truthful, or code snippets that we want to be executable.

Writing a loss function to capture these attributes seems intractable and most language models are still trained with a simple next token prediction loss (e.g. cross entropy). To compensate for the shortcomings of the loss itself people define metrics that are designed to better capture human preferences such as BLEU or ROUGE. While being better suited than the loss function itself at measuring performance these metrics simply compare generated text to references with simple rules and are thus also limited. Wouldn't it be great if we use human feedback for generated text as a measure of performance or go even one step further and use that feedback as a loss to optimize the model? That's the idea of Reinforcement Learning from Human Feedback (RLHF); use methods from reinforcement learning to directly optimize a language model with human feedback. RLHF has enabled language models to begin to align a model trained on a general corpus of text data to that of complex human values.

RLHF's most recent success was its use in ChatGPT. Given ChatGPT's impressive abilities, we asked it to explain RLHF for us:

It does surprisingly well, but doesn't quite cover everything. We'll fill in those gaps!

RLHF: Let’s take it step by step

Reinforcement learning from Human Feedback (also referenced as RL from human preferences) is a challenging concept because it involves a multiple-model training process and different stages of deployment. In this blog post, we’ll break down the training process into three core steps:

- Pretraining a language model (LM),

- gathering data and training a reward model, and

- fine-tuning the LM with reinforcement learning.

To start, we'll look at how language models are pretrained.

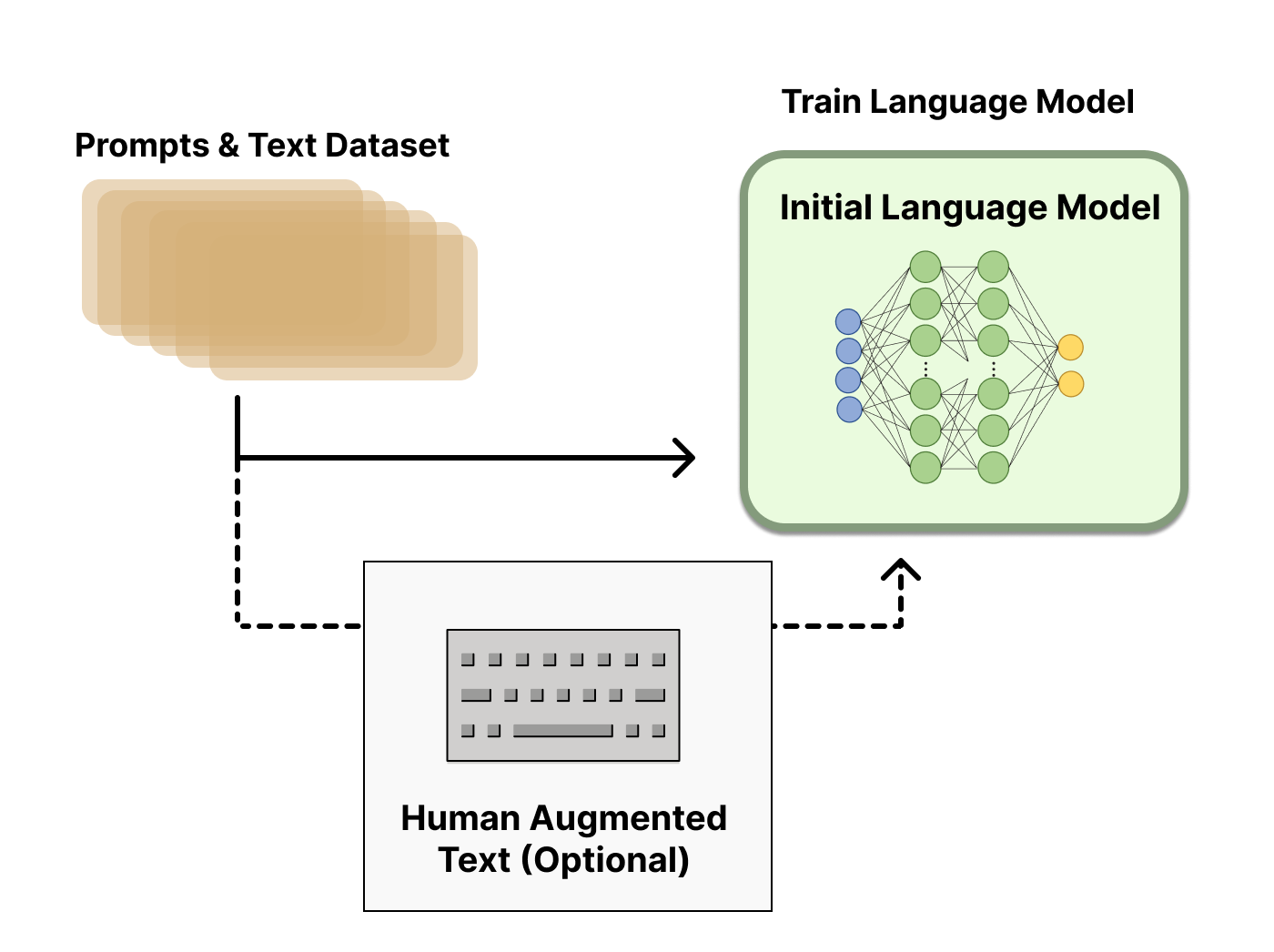

Pretraining language models

As a starting point RLHF use a language model that has already been pretrained with the classical pretraining objectives (see this blog post for more details). OpenAI used a smaller version of GPT-3 for its first popular RLHF model, InstructGPT. In their shared papers, Anthropic used transformer models from 10 million to 52 billion parameters trained for this task. DeepMind has documented using up to their 280 billion parameter model Gopher. It is likely that all these companies use much larger models in their RLHF-powered products.

This initial model can also be fine-tuned on additional text or conditions, but does not necessarily need to be. For example, OpenAI fine-tuned on human-generated text that was “preferable” and Anthropic generated their initial LM for RLHF by distilling an original LM on context clues for their “helpful, honest, and harmless” criteria. These are both sources of what we refer to as expensive, augmented data, but it is not a required technique to understand RLHF. Core to starting the RLHF process is having a model that responds well to diverse instructions.

In general, there is not a clear answer on “which model” is the best for the starting point of RLHF. This will be a common theme in this blog – the design space of options in RLHF training are not thoroughly explored.

Next, with a language model, one needs to generate data to train a reward model, which is how human preferences are integrated into the system.

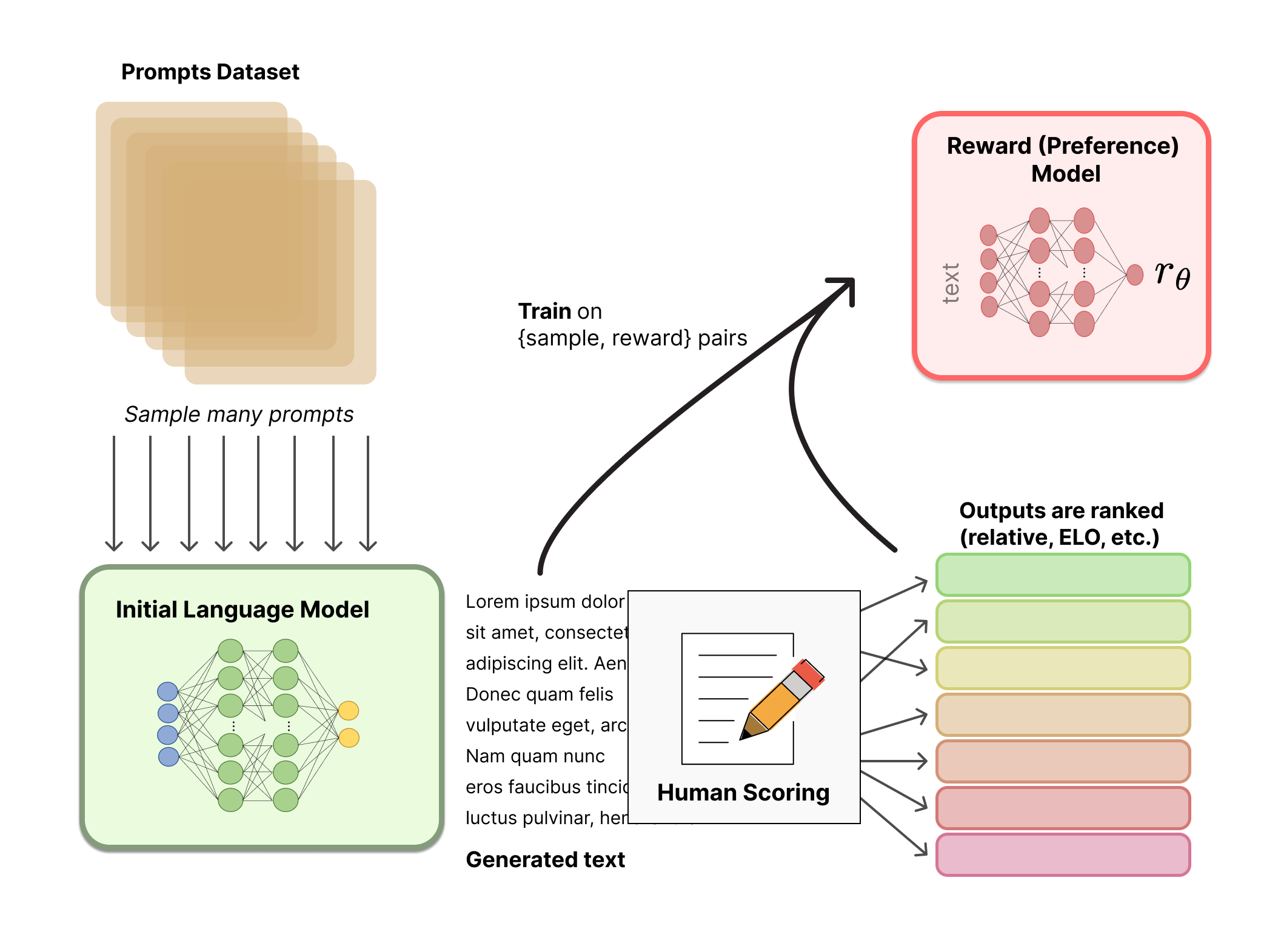

Reward model training

Generating a reward model (RM, also referred to as a preference model) calibrated with human preferences is where the relatively new research in RLHF begins. The underlying goal is to get a model or system that takes in a sequence of text, and returns a scalar reward which should numerically represent the human preference. The system can be an end-to-end LM, or a modular system outputting a reward (e.g. a model ranks outputs, and the ranking is converted to reward). The output being a scalar reward is crucial for existing RL algorithms being integrated seamlessly later in the RLHF process.

These LMs for reward modeling can be both another fine-tuned LM or a LM trained from scratch on the preference data. For example, Anthropic has used a specialized method of fine-tuning to initialize these models after pretraining (preference model pretraining, PMP) because they found it to be more sample efficient than fine-tuning, but no one base model is considered the clear best choice for reward models.

The training dataset of prompt-generation pairs for the RM is generated by sampling a set of prompts from a predefined dataset (Anthropic’s data generated primarily with a chat tool on Amazon Mechanical Turk is available on the Hub, and OpenAI used prompts submitted by users to the GPT API). The prompts are passed through the initial language model to generate new text.

Human annotators are used to rank the generated text outputs from the LM. One may initially think that humans should apply a scalar score directly to each piece of text in order to generate a reward model, but this is difficult to do in practice. The differing values of humans cause these scores to be uncalibrated and noisy. Instead, rankings are used to compare the outputs of multiple models and create a much better regularized dataset.

There are multiple methods for ranking the text. One method that has been successful is to have users compare generated text from two language models conditioned on the same prompt. By comparing model outputs in head-to-head matchups, an Elo system can be used to generate a ranking of the models and outputs relative to each-other. These different methods of ranking are normalized into a scalar reward signal for training.

An interesting artifact of this process is that the successful RLHF systems to date have used reward language models with varying sizes relative to the text generation (e.g. OpenAI 175B LM, 6B reward model, Anthropic used LM and reward models from 10B to 52B, DeepMind uses 70B Chinchilla models for both LM and reward). An intuition would be that these preference models need to have similar capacity to understand the text given to them as a model would need in order to generate said text.

At this point in the RLHF system, we have an initial language model that can be used to generate text and a preference model that takes in any text and assigns it a score of how well humans perceive it. Next, we use reinforcement learning (RL) to optimize the original language model with respect to the reward model.

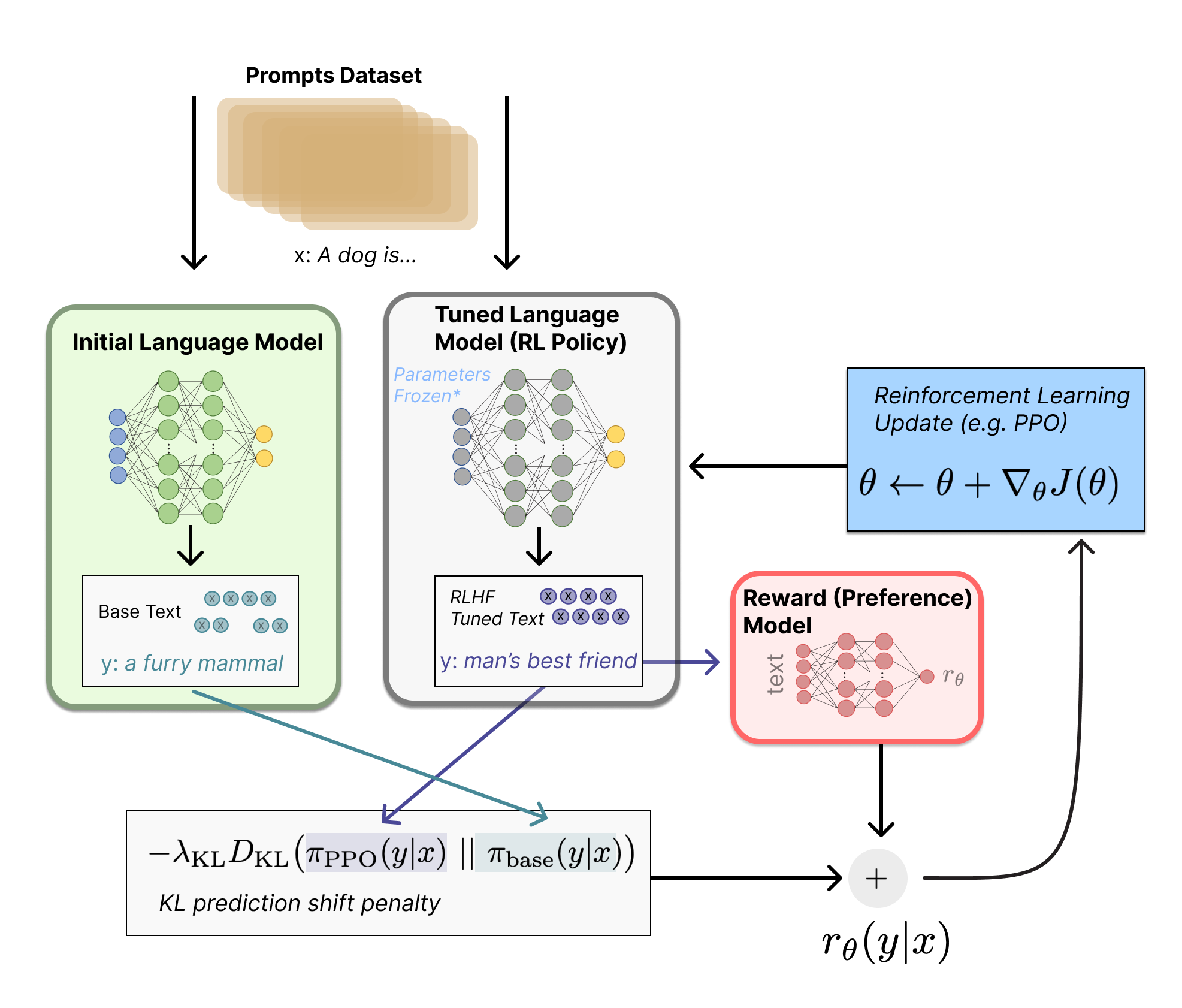

Fine-tuning with RL

Training a language model with reinforcement learning was, for a long time, something that people would have thought as impossible both for engineering and algorithmic reasons. What multiple organizations seem to have gotten to work is fine-tuning some or all of the parameters of a copy of the initial LM with a policy-gradient RL algorithm, Proximal Policy Optimization (PPO). Some parameters of the LM are frozen because fine-tuning an entire 10B or 100B+ parameter model is prohibitively expensive (for more, see Low-Rank Adaptation (LoRA) for LMs or the Sparrow LM from DeepMind) -- depending on the scale of the model and infrastructure being used. The exact dynamics of how many parameters to freeze, or not, is considered an open research problem. PPO has been around for a relatively long time – there are tons of guides on how it works. The relative maturity of this method made it a favorable choice for scaling up to the new application of distributed training for RLHF. It turns out that many of the core RL advancements to do RLHF have been figuring out how to update such a large model with a familiar algorithm (more on that later).

Let's first formulate this fine-tuning task as a RL problem. First, the policy is a language model that takes in a prompt and returns a sequence of text (or just probability distributions over text). The action space of this policy is all the tokens corresponding to the vocabulary of the language model (often on the order of 50k tokens) and the observation space is the distribution of possible input token sequences, which is also quite large given previous uses of RL (the dimension is approximately the size of vocabulary ^ length of the input token sequence). The reward function is a combination of the preference model and a constraint on policy shift.

The reward function is where the system combines all of the models we have discussed into one RLHF process. Given a prompt, x, from the dataset, the text y is generated by the current iteration of the fine-tuned policy. Concatenated with the original prompt, that text is passed to the preference model, which returns a scalar notion of “preferability”, . In addition, per-token probability distributions from the RL policy are compared to the ones from the initial model to compute a penalty on the difference between them. In multiple papers from OpenAI, Anthropic, and DeepMind, this penalty has been designed as a scaled version of the Kullback–Leibler (KL) divergence between these sequences of distributions over tokens, . The KL divergence term penalizes the RL policy from moving substantially away from the initial pretrained model with each training batch, which can be useful to make sure the model outputs reasonably coherent text snippets. Without this penalty the optimization can start to generate text that is gibberish but fools the reward model to give a high reward. In practice, the KL divergence is approximated via sampling from both distributions (explained by John Schulman here). The final reward sent to the RL update rule is .

Some RLHF systems have added additional terms to the reward function. For example, OpenAI experimented successfully on InstructGPT by mixing in additional pre-training gradients (from the human annotation set) into the update rule for PPO. It is likely as RLHF is further investigated, the formulation of this reward function will continue to evolve.

Finally, the update rule is the parameter update from PPO that maximizes the reward metrics in the current batch of data (PPO is on-policy, which means the parameters are only updated with the current batch of prompt-generation pairs). PPO is a trust region optimization algorithm that uses constraints on the gradient to ensure the update step does not destabilize the learning process. DeepMind used a similar reward setup for Gopher but used synchronous advantage actor-critic (A2C) to optimize the gradients, which is notably different but has not been reproduced externally.

Technical detail note: The above diagram makes it look like both models generate different responses for the same prompt, but what really happens is that the RL policy generates text, and that text is fed into the initial model to produce its relative probabilities for the KL penalty. This initial model is untouched by gradient updates during training.

Optionally, RLHF can continue from this point by iteratively updating the reward model and the policy together. As the RL policy updates, users can continue ranking these outputs versus the model's earlier versions. Most papers have yet to discuss implementing this operation, as the deployment mode needed to collect this type of data only works for dialogue agents with access to an engaged user base. Anthropic discusses this option as Iterated Online RLHF (see the original paper), where iterations of the policy are included in the ELO ranking system across models. This introduces complex dynamics of the policy and reward model evolving, which represents a complex and open research question.

Open-source tools for RLHF

The first code released to perform RLHF on LMs was from OpenAI in TensorFlow in 2019.

Today, there are already a few active repositories for RLHF in PyTorch that grew out of this. The primary repositories are Transformers Reinforcement Learning (TRL), TRLX which originated as a fork of TRL, and Reinforcement Learning for Language models (RL4LMs).

TRL is designed to fine-tune pretrained LMs in the Hugging Face ecosystem with PPO. TRLX is an expanded fork of TRL built by CarperAI to handle larger models for online and offline training. At the moment, TRLX has an API capable of production-ready RLHF with PPO and Implicit Language Q-Learning ILQL at the scales required for LLM deployment (e.g. 33 billion parameters). Future versions of TRLX will allow for language models up to 200B parameters. As such, interfacing with TRLX is optimized for machine learning engineers with experience at this scale.

RL4LMs offers building blocks for fine-tuning and evaluating LLMs with a wide variety of RL algorithms (PPO, NLPO, A2C and TRPO), reward functions and metrics. Moreover, the library is easily customizable, which allows training of any encoder-decoder or encoder transformer-based LM on any arbitrary user-specified reward function. Notably, it is well-tested and benchmarked on a broad range of tasks in recent work amounting up to 2000 experiments highlighting several practical insights on data budget comparison (expert demonstrations vs. reward modeling), handling reward hacking and training instabilities, etc. RL4LMs current plans include distributed training of larger models and new RL algorithms.

Both TRLX and RL4LMs are under heavy further development, so expect more features beyond these soon.

There is a large dataset created by Anthropic available on the Hub.

What’s next for RLHF?

While these techniques are extremely promising and impactful and have caught the attention of the biggest research labs in AI, there are still clear limitations. The models, while better, can still output harmful or factually inaccurate text without any uncertainty. This imperfection represents a long-term challenge and motivation for RLHF – operating in an inherently human problem domain means there will never be a clear final line to cross for the model to be labeled as complete.

When deploying a system using RLHF, gathering the human preference data is quite expensive due to the direct integration of other human workers outside the training loop. RLHF performance is only as good as the quality of its human annotations, which takes on two varieties: human-generated text, such as fine-tuning the initial LM in InstructGPT, and labels of human preferences between model outputs.

Generating well-written human text answering specific prompts is very costly, as it often requires hiring part-time staff (rather than being able to rely on product users or crowdsourcing). Thankfully, the scale of data used in training the reward model for most applications of RLHF (~50k labeled preference samples) is not as expensive. However, it is still a higher cost than academic labs would likely be able to afford. Currently, there only exists one large-scale dataset for RLHF on a general language model (from Anthropic) and a couple of smaller-scale task-specific datasets (such as summarization data from OpenAI). The second challenge of data for RLHF is that human annotators can often disagree, adding a substantial potential variance to the training data without ground truth.

With these limitations, huge swaths of unexplored design options could still enable RLHF to take substantial strides. Many of these fall within the domain of improving the RL optimizer. PPO is a relatively old algorithm, but there are no structural reasons that other algorithms could not offer benefits and permutations on the existing RLHF workflow. One large cost of the feedback portion of fine-tuning the LM policy is that every generated piece of text from the policy needs to be evaluated on the reward model (as it acts like part of the environment in the standard RL framework). To avoid these costly forward passes of a large model, offline RL could be used as a policy optimizer. Recently, new algorithms have emerged, such as implicit language Q-learning (ILQL) [Talk on ILQL at CarperAI], that fit particularly well with this type of optimization. Other core trade-offs in the RL process, like exploration-exploitation balance, have also not been documented. Exploring these directions would at least develop a substantial understanding of how RLHF functions and, if not, provide improved performance.

We hosted a lecture on Tuesday 13 December 2022 that expanded on this post; you can watch it here!

Further reading

Here is a list of the most prevalent papers on RLHF to date. The field was recently popularized with the emergence of DeepRL (around 2017) and has grown into a broader study of the applications of LLMs from many large technology companies. Here are some papers on RLHF that pre-date the LM focus:

- TAMER: Training an Agent Manually via Evaluative Reinforcement (Knox and Stone 2008): Proposed a learned agent where humans provided scores on the actions taken iteratively to learn a reward model.

- Interactive Learning from Policy-Dependent Human Feedback (MacGlashan et al. 2017): Proposed an actor-critic algorithm, COACH, where human feedback (both positive and negative) is used to tune the advantage function.

- Deep Reinforcement Learning from Human Preferences (Christiano et al. 2017): RLHF applied on preferences between Atari trajectories.

- Deep TAMER: Interactive Agent Shaping in High-Dimensional State Spaces (Warnell et al. 2018): Extends the TAMER framework where a deep neural network is used to model the reward prediction.

- A Survey of Preference-based Reinforcement Learning Methods (Wirth et al. 2017): Summarizes efforts above with many, many more references.

And here is a snapshot of the growing set of "key" papers that show RLHF's performance for LMs:

- Fine-Tuning Language Models from Human Preferences (Zieglar et al. 2019): An early paper that studies the impact of reward learning on four specific tasks.

- Learning to summarize with human feedback (Stiennon et al., 2020): RLHF applied to the task of summarizing text. Also, Recursively Summarizing Books with Human Feedback (OpenAI Alignment Team 2021), follow on work summarizing books.

- WebGPT: Browser-assisted question-answering with human feedback (OpenAI, 2021): Using RLHF to train an agent to navigate the web.

- InstructGPT: Training language models to follow instructions with human feedback (OpenAI Alignment Team 2022): RLHF applied to a general language model [Blog post on InstructGPT].

- GopherCite: Teaching language models to support answers with verified quotes (Menick et al. 2022): Train a LM with RLHF to return answers with specific citations.

- Sparrow: Improving alignment of dialogue agents via targeted human judgements (Glaese et al. 2022): Fine-tuning a dialogue agent with RLHF

- ChatGPT: Optimizing Language Models for Dialogue (OpenAI 2022): Training a LM with RLHF for suitable use as an all-purpose chat bot.

- Scaling Laws for Reward Model Overoptimization (Gao et al. 2022): studies the scaling properties of the learned preference model in RLHF.

- Training a Helpful and Harmless Assistant with Reinforcement Learning from Human Feedback (Anthropic, 2022): A detailed documentation of training a LM assistant with RLHF.

- Red Teaming Language Models to Reduce Harms: Methods, Scaling Behaviors, and Lessons Learned (Ganguli et al. 2022): A detailed documentation of efforts to “discover, measure, and attempt to reduce [language models] potentially harmful outputs.”

- Dynamic Planning in Open-Ended Dialogue using Reinforcement Learning (Cohen at al. 2022): Using RL to enhance the conversational skill of an open-ended dialogue agent.

- Is Reinforcement Learning (Not) for Natural Language Processing?: Benchmarks, Baselines, and Building Blocks for Natural Language Policy Optimization (Ramamurthy and Ammanabrolu et al. 2022): Discusses the design space of open-source tools in RLHF and proposes a new algorithm NLPO (Natural Language Policy Optimization) as an alternative to PPO.

- Llama 2 (Touvron et al. 2023): Impactful open-access model with substantial RLHF details.

The field is the convergence of multiple fields, so you can also find resources in other areas:

- Continual learning of instructions (Kojima et al. 2021, Suhr and Artzi 2022) or bandit learning from user feedback (Sokolov et al. 2016, Gao et al. 2022)

- Earlier history on using other RL algorithms for text generation (not all with human preferences), such as with recurrent neural networks (Ranzato et al. 2015), an actor-critic algorithm for text prediction (Bahdanau et al. 2016), or an early work adding human preferences to this framework (Nguyen et al. 2017).

Citation: If you found this useful for your academic work, please consider citing our work, in text:

Lambert, et al., "Illustrating Reinforcement Learning from Human Feedback (RLHF)", Hugging Face Blog, 2022.

BibTeX citation:

@article{lambert2022illustrating,

author = {Lambert, Nathan and Castricato, Louis and von Werra, Leandro and Havrilla, Alex},

title = {Illustrating Reinforcement Learning from Human Feedback (RLHF)},

journal = {Hugging Face Blog},

year = {2022},

note = {https://huggingface.co/blog/rlhf},

}

Thanks to Robert Kirk for fixing some factual errors regarding specific implementations of RLHF. Thanks to Stas Bekman for fixing some typos or confusing phrases Thanks to Peter Stone, Khanh X. Nguyen and Yoav Artzi for helping expand the related works further into history. Thanks to Igor Kotenkov for pointing out a technical error in the KL-penalty term of the RLHF procedure, its diagram, and textual description.