Add data for India National MO

#23

by

LxYxvv

- opened

This view is limited to 50 files because it contains too many changes.

See the raw diff here.

- INMO/download_script/download.py +75 -0

- INMO/md/en-2000.md +206 -0

- INMO/md/en-2001.md +211 -0

- INMO/md/en-2002.md +196 -0

- INMO/md/en-2003.md +194 -0

- INMO/md/en-2004.md +233 -0

- INMO/md/en-2005.md +354 -0

- INMO/md/en-2006.md +359 -0

- INMO/md/en-2007.md +349 -0

- INMO/md/en-2008.md +227 -0

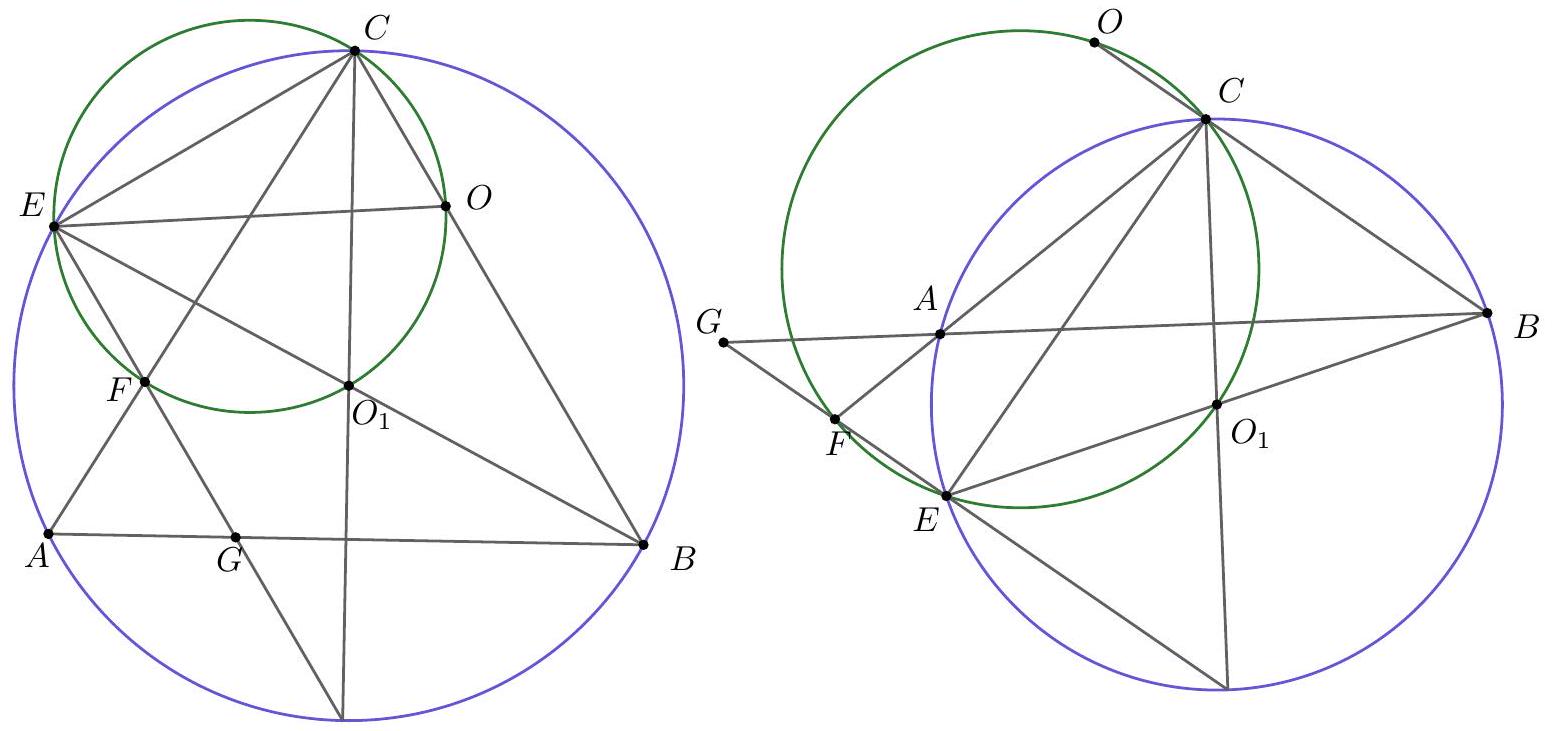

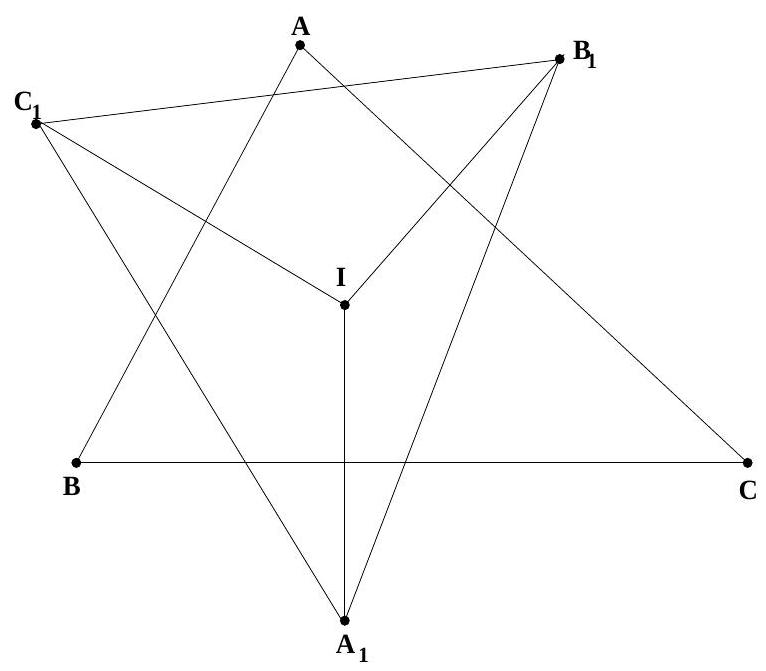

- INMO/md/en-2009.md +411 -0

- INMO/md/en-2010.md +270 -0

- INMO/md/en-2011.md +306 -0

- INMO/md/en-2012.md +307 -0

- INMO/md/en-2023.md +428 -0

- INMO/md/en-INMO_2021_solutions.md +370 -0

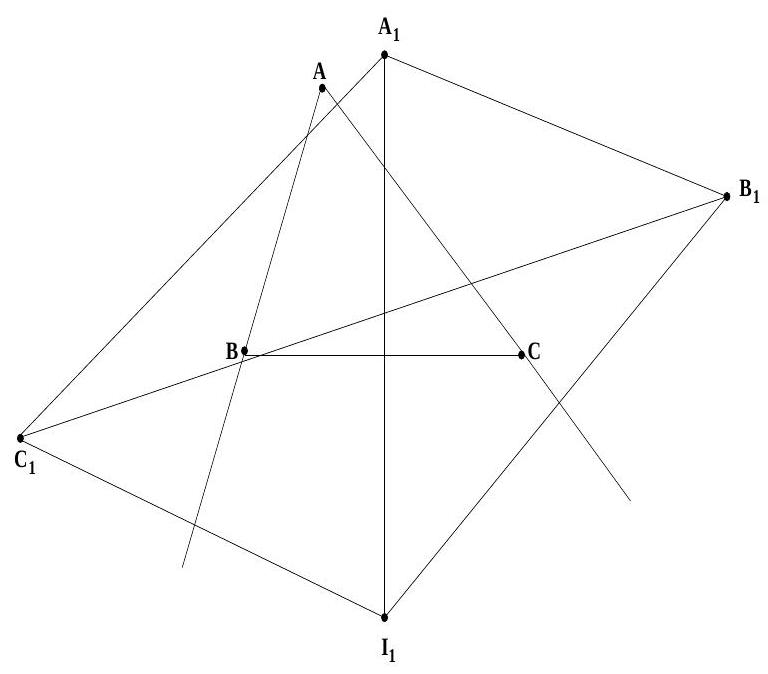

- INMO/md/en-INMO_2024_final_solutions.md +284 -0

- INMO/md/en-Inmo-2019-Solutions.md +225 -0

- INMO/md/en-inmo-2014.md +51 -0

- INMO/md/en-inmo2013-solutions.md +94 -0

- INMO/md/en-inmosol-15.md +261 -0

- INMO/md/en-sol-inmo-20.md +218 -0

- INMO/md/en-sol-inmo16.md +505 -0

- INMO/md/en-sol-inmo_17.md +418 -0

- INMO/raw/en-2000.pdf +3 -0

- INMO/raw/en-2001.pdf +3 -0

- INMO/raw/en-2002.pdf +3 -0

- INMO/raw/en-2003.pdf +3 -0

- INMO/raw/en-2004.pdf +3 -0

- INMO/raw/en-2005.pdf +3 -0

- INMO/raw/en-2006.pdf +3 -0

- INMO/raw/en-2007.pdf +3 -0

- INMO/raw/en-2008.pdf +3 -0

- INMO/raw/en-2009.pdf +3 -0

- INMO/raw/en-2010.pdf +3 -0

- INMO/raw/en-2011.pdf +3 -0

- INMO/raw/en-2012.pdf +3 -0

- INMO/raw/en-2023.pdf +3 -0

- INMO/raw/en-INMO_2021_solutions.pdf +3 -0

- INMO/raw/en-INMO_2024_final_solutions.pdf +3 -0

- INMO/raw/en-Inmo-2019-Solutions.pdf +3 -0

- INMO/raw/en-inmo-2014.pdf +3 -0

- INMO/raw/en-inmo2013-solutions.pdf +3 -0

- INMO/raw/en-inmosol-15.pdf +3 -0

- INMO/raw/en-sol-inmo-20.pdf +3 -0

- INMO/raw/en-sol-inmo16.pdf +3 -0

- INMO/raw/en-sol-inmo_17.pdf +3 -0

- INMO/segment_script/segment.py +127 -0

- INMO/segmented/en-2000.jsonl +6 -0

- INMO/segmented/en-2001.jsonl +6 -0

INMO/download_script/download.py

ADDED

|

@@ -0,0 +1,75 @@

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

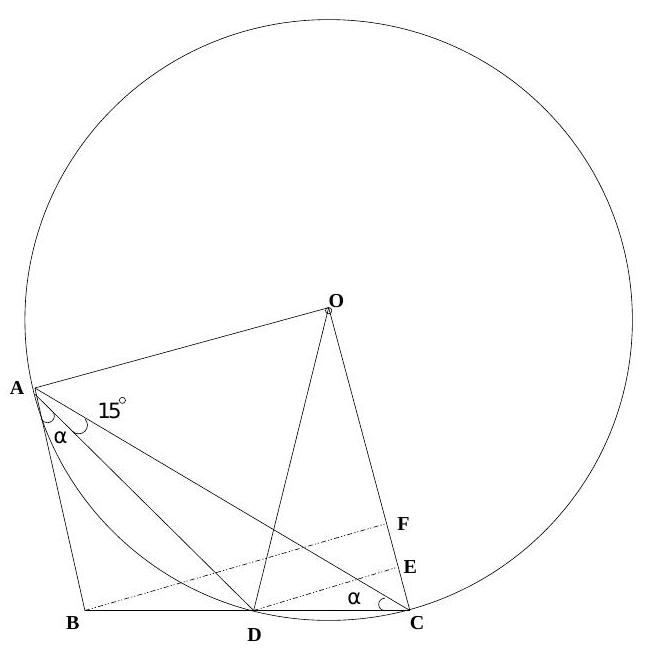

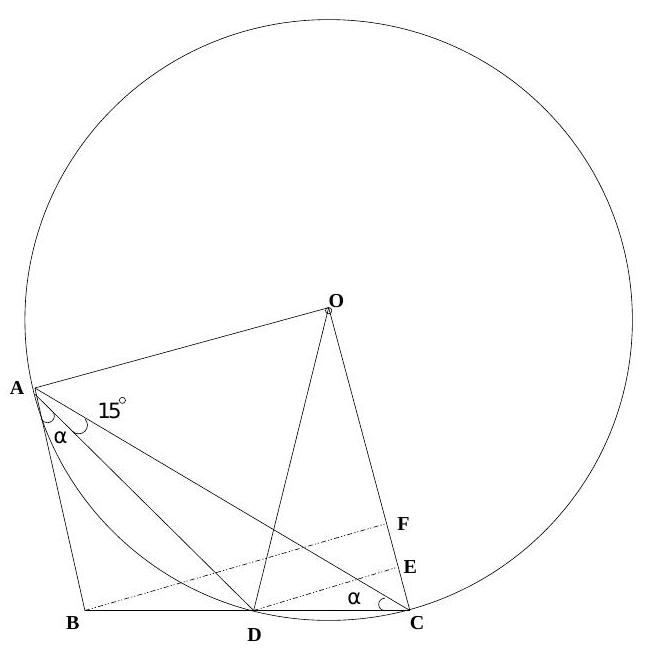

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 1 |

+

# -----------------------------------------------------------------------------

|

| 2 |

+

# Author: Jiawei Liu

|

| 3 |

+

# Date: 2024-12-24

|

| 4 |

+

# -----------------------------------------------------------------------------

|

| 5 |

+

'''

|

| 6 |

+

Download script for Nordic MO

|

| 7 |

+

To run:

|

| 8 |

+

`python INMo/download_script/download.py`

|

| 9 |

+

'''

|

| 10 |

+

|

| 11 |

+

import requests

|

| 12 |

+

from bs4 import BeautifulSoup

|

| 13 |

+

from tqdm import tqdm

|

| 14 |

+

from pathlib import Path

|

| 15 |

+

from requests.adapters import HTTPAdapter

|

| 16 |

+

from urllib3.util.retry import Retry

|

| 17 |

+

from urllib.parse import urljoin, unquote

|

| 18 |

+

|

| 19 |

+

|

| 20 |

+

def build_session(

|

| 21 |

+

max_retries: int = 3,

|

| 22 |

+

backoff_factor: int = 2,

|

| 23 |

+

session: requests.Session = None

|

| 24 |

+

) -> requests.Session:

|

| 25 |

+

"""

|

| 26 |

+

Build a requests session with retries

|

| 27 |

+

|

| 28 |

+

Args:

|

| 29 |

+

max_retries (int, optional): Number of retries. Defaults to 3.

|

| 30 |

+

backoff_factor (int, optional): Backoff factor. Defaults to 2.

|

| 31 |

+

session (requests.Session, optional): Session object. Defaults to None.

|

| 32 |

+

"""

|

| 33 |

+

session = session or requests.Session()

|

| 34 |

+

adapter = HTTPAdapter(max_retries=Retry(total=max_retries, backoff_factor=backoff_factor))

|

| 35 |

+

session.mount("http://", adapter)

|

| 36 |

+

session.mount("https://", adapter)

|

| 37 |

+

session.headers.update({

|

| 38 |

+

"User-Agent": "Mozilla/5.0 (Windows NT 10.0; Win64; x64) AppleWebKit/537.36 (KHTML, like Gecko) Chrome/58.0.3029.110 Safari/537.3"

|

| 39 |

+

})

|

| 40 |

+

|

| 41 |

+

return session

|

| 42 |

+

|

| 43 |

+

|

| 44 |

+

def main():

|

| 45 |

+

base_url = "https://olympiads.hbcse.tifr.res.in/how-to-prepare/past-papers/"

|

| 46 |

+

req_session = build_session()

|

| 47 |

+

|

| 48 |

+

output_dir = Path(__file__).parent.parent / "raw"

|

| 49 |

+

output_dir.mkdir(parents=True, exist_ok=True)

|

| 50 |

+

|

| 51 |

+

resp = req_session.get(base_url)

|

| 52 |

+

soup = BeautifulSoup(resp.text, 'html.parser')

|

| 53 |

+

|

| 54 |

+

link_eles = soup.find_all('a', href=lambda x: x.endswith(".pdf") and "inmo" in x.lower())

|

| 55 |

+

|

| 56 |

+

links = [ele["href"] for ele in link_eles]

|

| 57 |

+

|

| 58 |

+

for url in tqdm(links):

|

| 59 |

+

output_file = output_dir / f"en-{unquote(Path(url).name)}"

|

| 60 |

+

|

| 61 |

+

# Check if the file already exists

|

| 62 |

+

if output_file.exists():

|

| 63 |

+

continue

|

| 64 |

+

|

| 65 |

+

pdf_resp = req_session.get(urljoin(base_url, url))

|

| 66 |

+

|

| 67 |

+

if pdf_resp.status_code != 200:

|

| 68 |

+

print(f"Failed to download {url}")

|

| 69 |

+

continue

|

| 70 |

+

|

| 71 |

+

output_file.write_bytes(pdf_resp.content)

|

| 72 |

+

|

| 73 |

+

|

| 74 |

+

if __name__ == "__main__":

|

| 75 |

+

main()

|

INMO/md/en-2000.md

ADDED

|

@@ -0,0 +1,206 @@

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 1 |

+

# INMO-2000 <br> Problems and Solutions

|

| 2 |

+

|

| 3 |

+

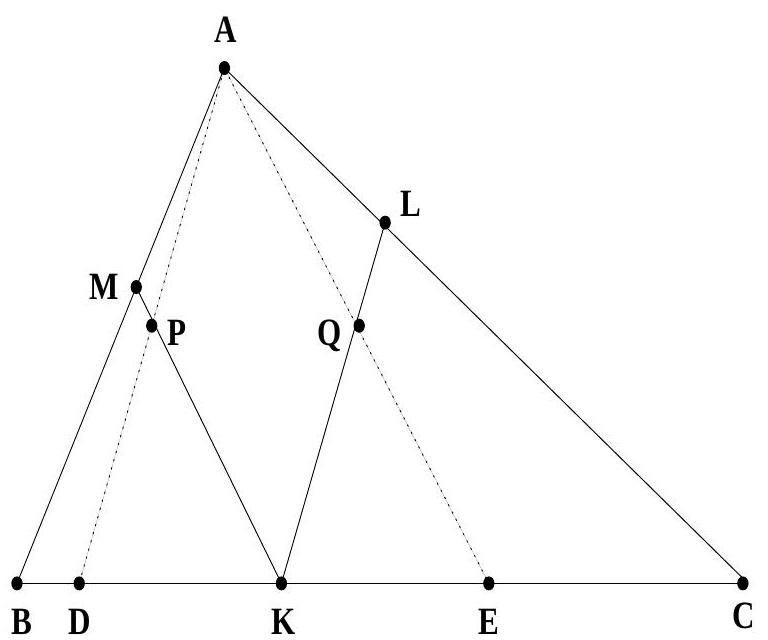

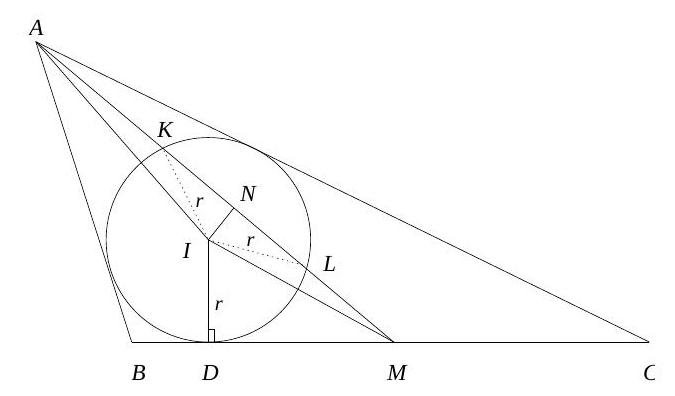

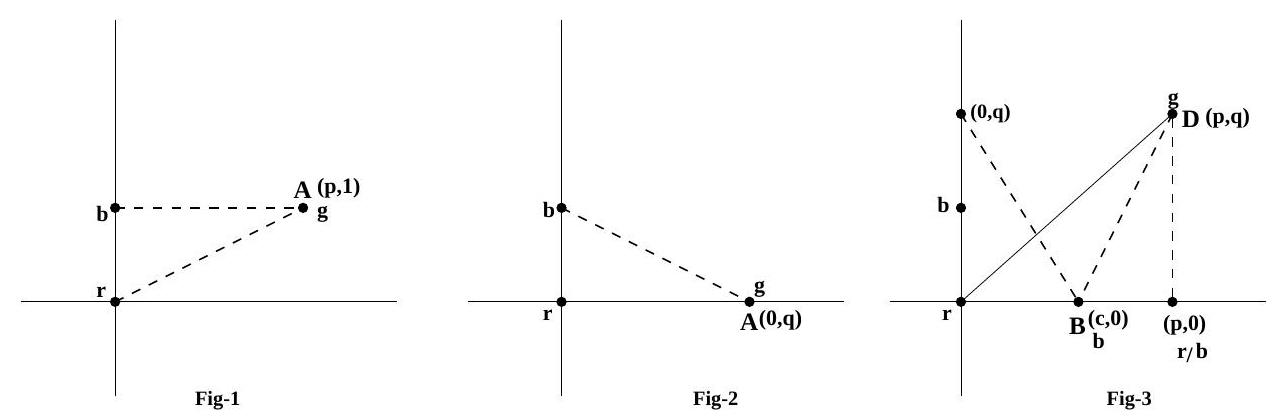

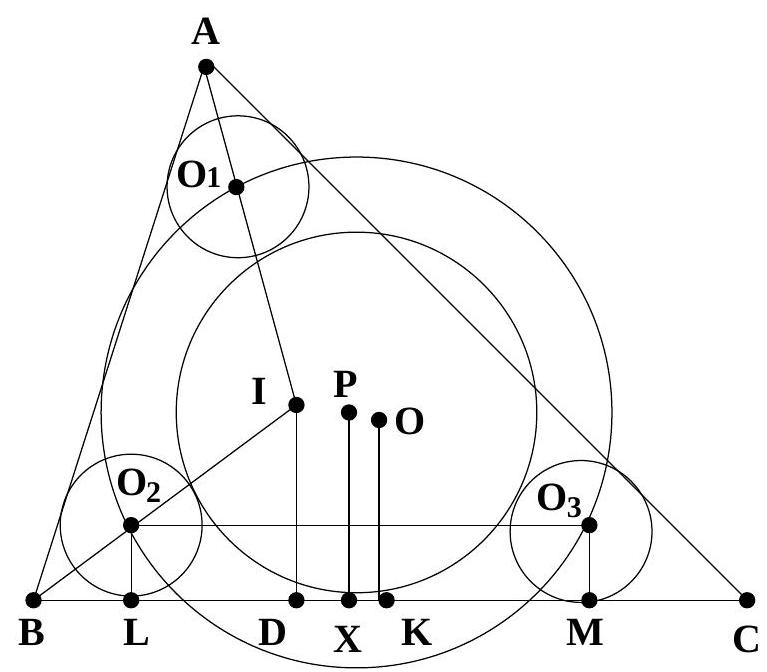

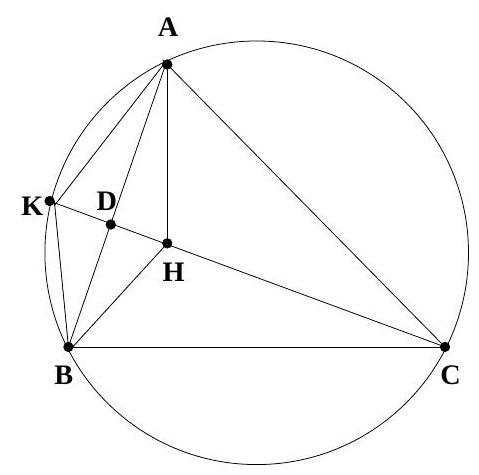

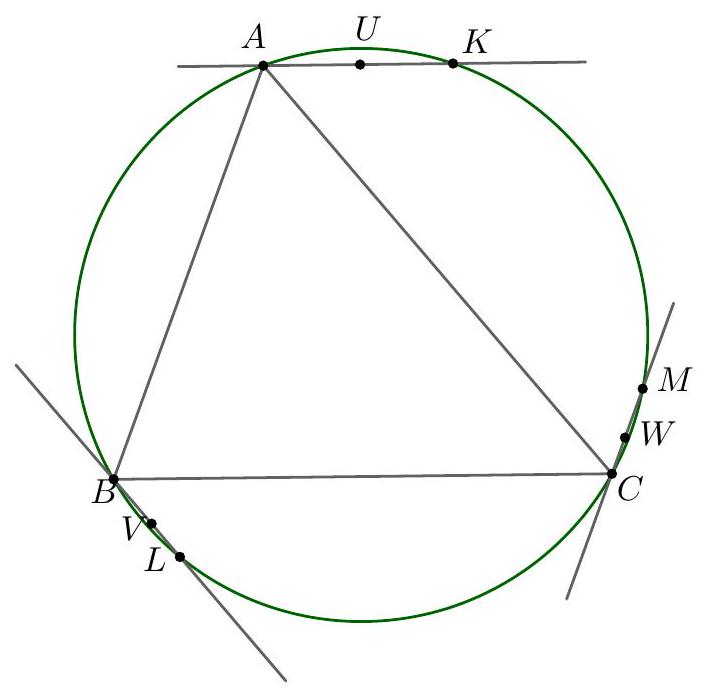

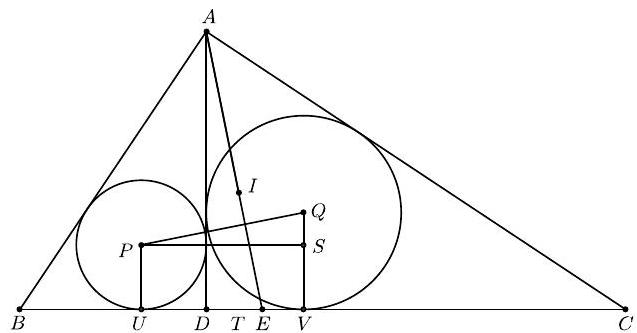

1. The in-circle of triangle $A B C$ touches the sides $B C, C A$ and $A B$ in $K, L$ and $M$ respectively. The line through $A$ and parallel to $L K$ meets $M K$ in $P$ and the line through $A$ and parallel to $M K$ meets $L K$ in $Q$. Show that the line $P Q$ bisects the sides $A B$ and $A C$ of triangle $A B C$.

|

| 4 |

+

|

| 5 |

+

Solution. : Let $A P, A Q$ produced meet $B C$ in $D, E$ respectively.

|

| 6 |

+

|

| 7 |

+

|

| 8 |

+

|

| 9 |

+

Since $M K$ is parallel to $A E$, we have $\angle A E K=\angle M K B$. Since $B K=B M$, both being tangents to the circle from $B, \angle M K B=\angle B M K$. This with the fact that $M K$ is parallel to $A E$ gives us $\angle A E K=\angle M A E$. This shows that $M A E K$ is an isosceles trapezoid. We conclude that $M A=K E$. Similarly, we can prove that $A L=D K$. But $A M=A L$. We get that $D K=K E$. Since $K P$ is parallel to $A E$, we get $D P=P A$ and similarly $E Q=Q A$. This implies that $P Q$ is parallel to $D E$ and hence bisects $A B, A C$ when produced.

|

| 10 |

+

|

| 11 |

+

[The same argument holds even if one or both of $P$ and $Q$ lie outside triangle $A B C$.]

|

| 12 |

+

|

| 13 |

+

2. Solve for integers $x, y, z$ :

|

| 14 |

+

|

| 15 |

+

$$

|

| 16 |

+

x+y=1-z, \quad x^{3}+y^{3}=1-z^{2}

|

| 17 |

+

$$

|

| 18 |

+

|

| 19 |

+

Sol. : Eliminating $z$ from the given set of equations, we get

|

| 20 |

+

|

| 21 |

+

$$

|

| 22 |

+

x^{3}+y^{3}+\{1-(x+y)\}^{2}=1

|

| 23 |

+

$$

|

| 24 |

+

|

| 25 |

+

This factors to

|

| 26 |

+

|

| 27 |

+

$$

|

| 28 |

+

(x+y)\left(x^{2}-x y+y^{2}+x+y-2\right)=0

|

| 29 |

+

$$

|

| 30 |

+

|

| 31 |

+

Case 1. Suppose $x+y=0$. Then $z=1$ and $(x, y, z)=(m,-m, 1)$, where $m$ is an integer give one family of solutions.

|

| 32 |

+

|

| 33 |

+

Case 2. Suppose $x+y \neq 0$. Then we must have

|

| 34 |

+

|

| 35 |

+

$$

|

| 36 |

+

x^{2}-x y+y^{2}+x+y-2=0 \text {. }

|

| 37 |

+

$$

|

| 38 |

+

|

| 39 |

+

This can be written in the form

|

| 40 |

+

|

| 41 |

+

$$

|

| 42 |

+

(2 x-y+1)^{2}+3(y+1)^{2}=12

|

| 43 |

+

$$

|

| 44 |

+

|

| 45 |

+

Here there are two possibilities:

|

| 46 |

+

|

| 47 |

+

$$

|

| 48 |

+

2 x-y+1=0, y+1= \pm 2 ; \quad 2 x-y+1= \pm 3, y+1= \pm 1

|

| 49 |

+

$$

|

| 50 |

+

|

| 51 |

+

Analysing all these cases we get

|

| 52 |

+

|

| 53 |

+

$$

|

| 54 |

+

(x, y, z)=(0,1,0),(-2,-3,6),(1,0,0),(0,-2,3),(-2,0,3),(-3,-2,6) .

|

| 55 |

+

$$

|

| 56 |

+

|

| 57 |

+

3. If $a, b, c, x$ are real numbers such that $a b c \neq 0$ and

|

| 58 |

+

|

| 59 |

+

$$

|

| 60 |

+

\frac{x b+(1-x) c}{a}=\frac{x c+(1-x) a}{b}=\frac{x a+(1-x) b}{c}

|

| 61 |

+

$$

|

| 62 |

+

|

| 63 |

+

then prove that either $a+b+c=0$ or $a=b=c$.

|

| 64 |

+

|

| 65 |

+

Sol. : Suppose $a+b+c \neq 0$ and let the common value be $\lambda$. Then

|

| 66 |

+

|

| 67 |

+

$$

|

| 68 |

+

\lambda=\frac{x b+(1-x) c+x c+(1-x) a+x a+(1-x) b}{a+b+c}=1

|

| 69 |

+

$$

|

| 70 |

+

|

| 71 |

+

We get two equations:

|

| 72 |

+

|

| 73 |

+

$$

|

| 74 |

+

-a+x b+(1-x) c=0, \quad(1-x) a-b+x c=0

|

| 75 |

+

$$

|

| 76 |

+

|

| 77 |

+

(The other equation is a linear combination of these two.) Using these two equations, we get the relations

|

| 78 |

+

|

| 79 |

+

$$

|

| 80 |

+

\frac{a}{1-x+x^{2}}=\frac{b}{x^{2}-x+1}=\frac{c}{(1-x)^{2}+x}

|

| 81 |

+

$$

|

| 82 |

+

|

| 83 |

+

Since $1-x+x^{2} \neq 0$, we get $a=b=c$.

|

| 84 |

+

|

| 85 |

+

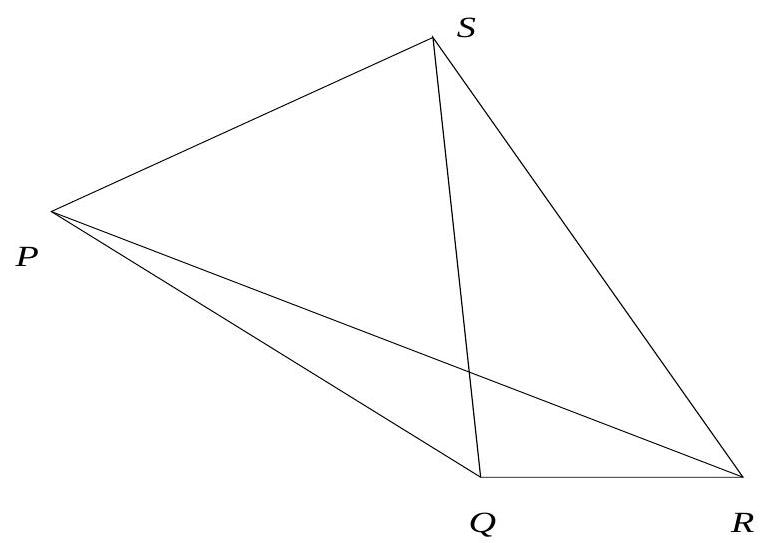

4. In a convex quadrilateral $P Q R S, P Q=R S,(\sqrt{3}+1) Q R=S P$ and $\angle R S P-\angle S P Q=$ $30^{\circ}$. Prove that

|

| 86 |

+

|

| 87 |

+

$$

|

| 88 |

+

\angle P Q R-\angle Q R S=90^{\circ}

|

| 89 |

+

$$

|

| 90 |

+

|

| 91 |

+

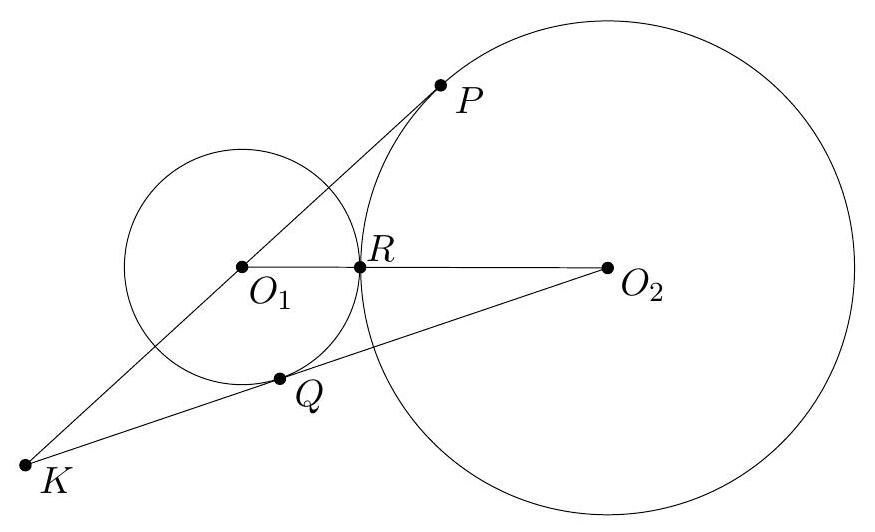

Sol. : Let $[$ Fig $]$ denote the area of Fig. We have

|

| 92 |

+

|

| 93 |

+

$$

|

| 94 |

+

[P Q R S]=[P Q R]+[R S P]=[Q R S]+[S P Q]

|

| 95 |

+

$$

|

| 96 |

+

|

| 97 |

+

Let us write $P Q=p, Q R=q, R S=r, S P=s$. The above relations reduce to

|

| 98 |

+

|

| 99 |

+

$$

|

| 100 |

+

p q \sin \angle P Q R+r s \sin \angle R S P=q r \sin \angle Q R S+s p \sin \angle S P Q

|

| 101 |

+

$$

|

| 102 |

+

|

| 103 |

+

Using $p=r$ and $(\sqrt{3}+1) q=s$ and dividing by $p q$, we get

|

| 104 |

+

|

| 105 |

+

$$

|

| 106 |

+

\sin \angle P Q R+(\sqrt{3}+1) \sin \angle R S P=\sin \angle Q R S+(\sqrt{3}+1) \sin \angle S P Q

|

| 107 |

+

$$

|

| 108 |

+

|

| 109 |

+

Therefore, $\sin \angle P Q R-\sin \angle Q R S=(\sqrt{3}+1)(\sin \angle S P Q-\sin \angle R S P)$.

|

| 110 |

+

|

| 111 |

+

|

| 112 |

+

|

| 113 |

+

Fig. 2.

|

| 114 |

+

|

| 115 |

+

This can be written in the form

|

| 116 |

+

|

| 117 |

+

$$

|

| 118 |

+

\begin{aligned}

|

| 119 |

+

2 \sin & \frac{\angle P Q R-\angle Q R S}{2} \cos \frac{\angle P Q R+\angle Q R S}{2} \\

|

| 120 |

+

& =(\sqrt{3}+1) 2 \sin \frac{\angle S P Q-\angle R S P}{2} \cos \frac{\angle S P Q+\angle R S P}{2}

|

| 121 |

+

\end{aligned}

|

| 122 |

+

$$

|

| 123 |

+

|

| 124 |

+

Using the relations

|

| 125 |

+

|

| 126 |

+

$$

|

| 127 |

+

\cos \frac{\angle P Q R+\angle Q R S}{2}=-\cos \frac{\angle S P Q+\angle R S P}{2}

|

| 128 |

+

$$

|

| 129 |

+

|

| 130 |

+

and

|

| 131 |

+

|

| 132 |

+

$$

|

| 133 |

+

\sin \frac{\angle S P Q-\angle R S P}{2}=-\sin 15^{\circ}=-\frac{(\sqrt{3}-1)}{2 \sqrt{2}}

|

| 134 |

+

$$

|

| 135 |

+

|

| 136 |

+

we obtain

|

| 137 |

+

|

| 138 |

+

$$

|

| 139 |

+

\sin \frac{\angle P Q R-\angle Q R S}{2}=(\sqrt{3}+1)\left[-\frac{(\sqrt{3}-1)}{2 \sqrt{2}}\right]=\frac{1}{\sqrt{2}}

|

| 140 |

+

$$

|

| 141 |

+

|

| 142 |

+

This shows that

|

| 143 |

+

|

| 144 |

+

$$

|

| 145 |

+

\frac{\angle P Q R-\angle Q R S}{2}=\frac{\pi}{4} \quad \text { or } \quad \frac{3 \pi}{4}

|

| 146 |

+

$$

|

| 147 |

+

|

| 148 |

+

Using the convexity of $P Q R S$, we can rule out the latter alternative. We obtain

|

| 149 |

+

|

| 150 |

+

$$

|

| 151 |

+

\angle P Q R-\angle Q R S=\frac{\pi}{2}

|

| 152 |

+

$$

|

| 153 |

+

|

| 154 |

+

5. Let $a, b, c$ be three real numbers such that $1 \geq a \geq b \geq c \geq 0$. Prove that if $\lambda$ is a root of the cubic equation $x^{3}+a x^{2}+b x+c=0$ (real or complex), then $|\lambda| \leq 1$.

|

| 155 |

+

|

| 156 |

+

Sol. : Since $\lambda$ is a root of the equation $x^{3}+a x^{2}+b x+c=0$, we have

|

| 157 |

+

|

| 158 |

+

$$

|

| 159 |

+

\lambda^{3}=-a \lambda^{2}-b \lambda-c

|

| 160 |

+

$$

|

| 161 |

+

|

| 162 |

+

This implies that

|

| 163 |

+

|

| 164 |

+

$$

|

| 165 |

+

\begin{aligned}

|

| 166 |

+

\lambda^{4} & =-a \lambda^{3}-b \lambda^{2}-c \lambda \\

|

| 167 |

+

& =(1-a) \lambda^{3}+(a-b) \lambda^{2}+(b-c) \lambda+c

|

| 168 |

+

\end{aligned}

|

| 169 |

+

$$

|

| 170 |

+

|

| 171 |

+

where we have used again

|

| 172 |

+

|

| 173 |

+

$$

|

| 174 |

+

-\lambda^{3}-a \lambda^{2}-b \lambda-c=0

|

| 175 |

+

$$

|

| 176 |

+

|

| 177 |

+

Suppose $|\lambda| \geq 1$. Then we obtain

|

| 178 |

+

|

| 179 |

+

$$

|

| 180 |

+

\begin{aligned}

|

| 181 |

+

|\lambda|^{4} & \leq(1-a)|\lambda|^{3}+(a-b)|\lambda|^{2}+(b-c)|\lambda|+c \\

|

| 182 |

+

& \leq(1-a)|\lambda|^{3}+(a-b)|\lambda|^{3}+(b-c)|\lambda|^{3}+c|\lambda|^{3} \\

|

| 183 |

+

& \leq|\lambda|^{3}

|

| 184 |

+

\end{aligned}

|

| 185 |

+

$$

|

| 186 |

+

|

| 187 |

+

This shows that $|\lambda| \leq 1$. Hence the only possibility in this case is $|\lambda|=1$. We conclude that $|\lambda| \leq 1$ is always true.

|

| 188 |

+

|

| 189 |

+

6. For any natural number $n,(n \geq 3)$, let $f(n)$ denote the number of non-congruent integer-sided triangles with perimeter $n$ (e.g., $f(3)=1, f(4)=0, f(7)=2$ ). Show that

|

| 190 |

+

|

| 191 |

+

(a) $f(1999)>f(1996)$

|

| 192 |

+

|

| 193 |

+

(b) $f(2000)=f(1997)$.

|

| 194 |

+

|

| 195 |

+

Sol. :

|

| 196 |

+

|

| 197 |

+

(a) Let $a, b, c$ be the sides of a triangle with $a+b+c=1996$, and each being a positive integer. Then $a+1, b+1, c+1$ are also sides of a triangle with perimeter 1999 because

|

| 198 |

+

|

| 199 |

+

$$

|

| 200 |

+

a<b+c \quad \Longrightarrow \quad a+1<(b+1)+(c+1)

|

| 201 |

+

$$

|

| 202 |

+

|

| 203 |

+

and so on. Moreover $(999,999,1)$ form the sides of a triangle with perimeter 1999, which is not obtainable in the form $(a+1, b+1, c+1)$ where $a, b, c$ are the integers and the sides of a triangle with $a+b+c=1996$. We conclude that $f(1999)>f(1996)$.

|

| 204 |

+

|

| 205 |

+

(b) As in the case (a) we conclude that $f(2000) \geq f(1997)$. On the other hand, if $x, y, z$ are the integer sides of a triangle with $x+y+z=2000$, and say $x \geq y \geq z \geq 1$, then we cannot have $z=1$; for otherwise we would get $x+y=1999$ forcing $x, y$ to have opposite parity so that $x-y \geq 1=z$ violating triangle inequality for $x, y, z$. Hence $x \geq y \geq z>1$. This implies that $x-1 \geq y-1 \geq z-1>0$. We already have $x<y+z$. If $x \geq y+z-1$, then we see that $y+z-1 \leq x<y+z$, showing that $y+z-1=x$. Hence we obtain $2000=x+y+z=2 x+1$ which is impossible. We conclude that $x<y+z-1$. This shows that $x-1<(y-1)+(z-1)$ and hence $x-1, y-1, z-1$ are the sides of a triangle with perimeter 1997. This gives $f(2000) \leq f(1997)$. Thus we obtain the desired result.

|

| 206 |

+

|

INMO/md/en-2001.md

ADDED

|

@@ -0,0 +1,211 @@

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 1 |

+

# INMO-2001 <br> Problems and Solutions

|

| 2 |

+

|

| 3 |

+

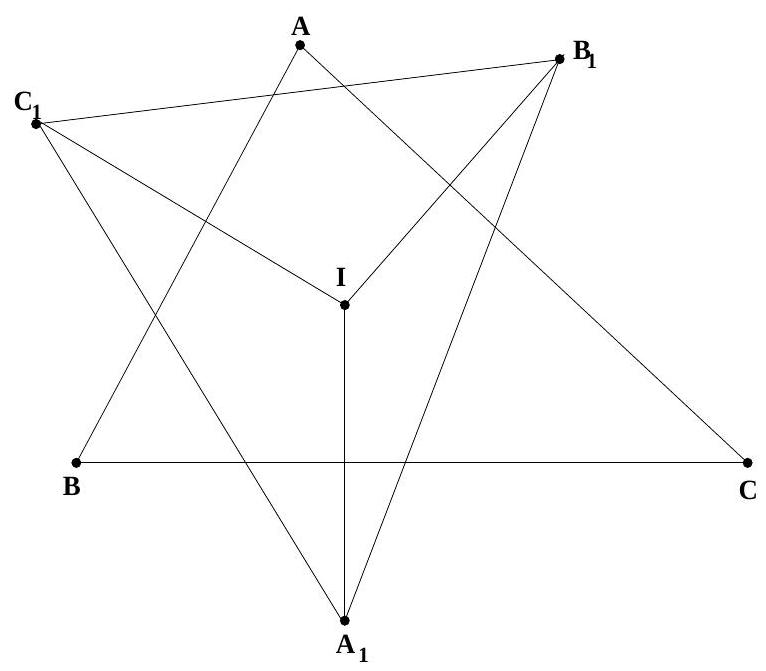

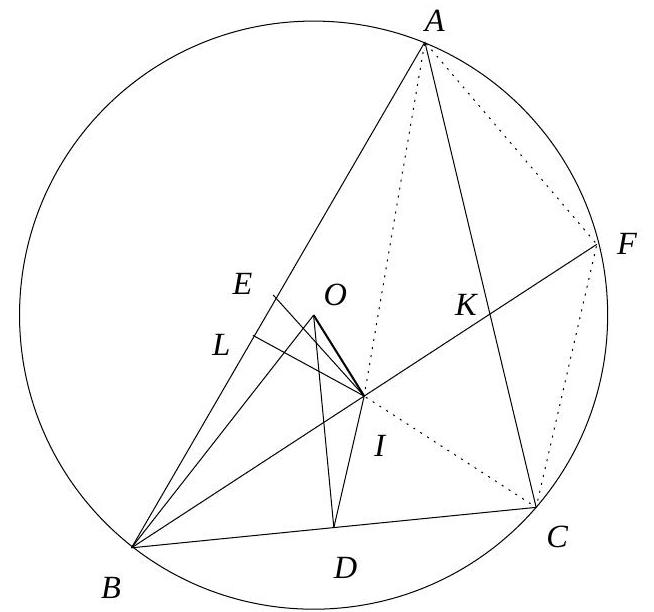

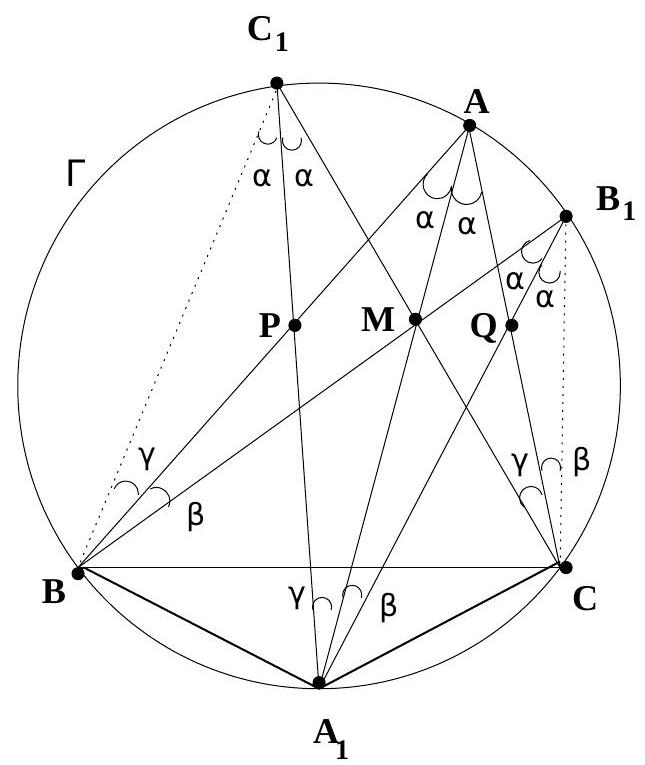

1. Let $A B C$ be a triangle in which no angle is $90^{\circ}$. For any point $P$ in the plane of the triangle, let $A_{1}, B_{1}, C_{1}$ denote the reflections of $P$ in the sides $B C, C A, A B$ respectively. Prove the following statements:

|

| 4 |

+

|

| 5 |

+

(a) If $P$ is the incentre or an excentre of $A B C$, then $P$ is the circumcentre of $A_{1} B_{1} C_{1}$;

|

| 6 |

+

|

| 7 |

+

(b) If $P$ is the circumcentre of $A B C$, then $P$ is the orthocentre of $A_{1} B_{1} C_{1}$;

|

| 8 |

+

|

| 9 |

+

(c) If $P$ is the orthocentre of $A B C$, then $P$ is either the incentre or an excentre of $A_{1} B_{1} C_{1}$.

|

| 10 |

+

|

| 11 |

+

## Solution:

|

| 12 |

+

|

| 13 |

+

(a)

|

| 14 |

+

|

| 15 |

+

|

| 16 |

+

|

| 17 |

+

If $P=I$ is the incentre of triangle $A B C$, and $r$ its inradius, then it is clear that $A_{1} I=B_{1} I=C_{1} I=2 r$. It follows that $I$ is the circumcentre of $A_{1} B_{1} C_{1}$. On the otherhand if $P=I_{1}$ is the excentre of $A B C$ opposite $A$ and $r_{1}$ the corresponding exradius, then again we see that $A_{1} I_{1}=B_{1} I_{1}=C_{1} I_{1}=2 r_{1}$. Thus $I_{1}$ is the circumcentre of $A_{1} B_{1} C_{1}$.

|

| 18 |

+

|

| 19 |

+

|

| 20 |

+

|

| 21 |

+

(b)

|

| 22 |

+

|

| 23 |

+

Let $P=O$ be the circumcentre of $A B C$. By definition, it follows that $O A_{1}$ bisects and is bisected by $B C$ and so on. Let $D, E, F$ be the mid-points of $B C, C A, A B$ respectively. Then $F E$ is parallel to $B C$. But $E, F$ are also mid-points of $O B_{1}, O C_{1}$ and hence $F E$ is parallel to $B_{1} C_{1}$ as well. We conclude that $B C$ is parallel to $B_{1} C_{1}$. Since $O A_{1}$ is perpendicular to $B C$, it follows that $O A_{1}$ is perpendicular to $B_{1} C_{1}$. Similarly $O B_{1}$ is perpendicular to $C_{1} A_{1}$ and $O C_{1}$ is perpendicular to $A_{1} B_{1}$. These imply that $O$ is the orthocentre of $A_{1} B_{1} C_{1}$. (This applies whether $O$ is inside or outside $A B C$.)

|

| 24 |

+

|

| 25 |

+

(c)

|

| 26 |

+

|

| 27 |

+

let $P=H$, the orthocentre of $A B C$. We consider two possibilities; $H$ falls inside $A B C$ and $H$ falls outside $A B C$.

|

| 28 |

+

|

| 29 |

+

Suppose $H$ is inside $A B C$; this happens if $A B C$ is an acute triangle. It is known that $A_{1}, B_{1}, C_{1}$ lie on the circumcircle of $A B C$. Thus $\angle C_{1} A_{1} A=\angle C_{1} C A=90^{\circ}-A$. Similarly $\angle B_{1} A_{1} A=\angle B_{1} B A=90^{\circ}-A$. These show that $\angle C_{1} A_{1} A=\angle B_{1} A_{1} A$. Thus $A_{1} A$ is an internal bisector of $\angle C_{1} A_{1} B_{1}$. Similarly we can show that $B_{1}$ bisects $\angle A_{1} B_{1} C_{1}$ and $C_{1} C$ bisects $\angle B_{1} C_{1} A_{1}$. Since $A_{1} A, B_{1} B, C_{1} C$ concur at $H$, we conclude that $H$ is the incentre of $A_{1} B_{1} C_{1}$.

|

| 30 |

+

|

| 31 |

+

OR If $D, E, F$ are the feet of perpendiculars of $A, B, C$ to the sides $B C, C A, A B$ respectively, then we see that $E F, F D, D E$ are respectively parallel to $B_{1} C_{1}, C_{1} A_{1}$, $A_{1} B_{1}$. This implies that $\angle C_{1} A_{1} H=\angle F D H=\angle A B E=90^{\circ}-A$, as $B D H F$ is a cyclic quadrilateral. Similarly, we can show that $\angle B_{1} A_{1} H=90^{\circ}-A$. It follows that $A_{1} H$ is the internal bisector of $\angle C_{1} A_{1} B_{1}$. We can proceed as in the earlier case.

|

| 32 |

+

|

| 33 |

+

If $H$ is outside $A B C$, the same proofs go through again, except that two of $A_{1} H$, $B_{1} H, C_{1} H$ are external angle bisectors and one of these is an internal angle bisector. Thus $H$ becomes an excentre of triangle $A_{1} B_{1} C_{1}$.

|

| 34 |

+

|

| 35 |

+

2. Show that the equation

|

| 36 |

+

|

| 37 |

+

$$

|

| 38 |

+

x^{2}+y^{2}+z^{2}=(x-y)(y-z)(z-x)

|

| 39 |

+

$$

|

| 40 |

+

|

| 41 |

+

has infinitely many solutions in integers $x, y, z$.

|

| 42 |

+

|

| 43 |

+

Solution: We seek solutions $(x, y, z)$ which are in arithmetic progression. Let us put $y-x=z-y=d>0$ so that the equation reduces to the form

|

| 44 |

+

|

| 45 |

+

$$

|

| 46 |

+

3 y^{2}+2 d^{2}=2 d^{3}

|

| 47 |

+

$$

|

| 48 |

+

|

| 49 |

+

Thus we get $3 y^{2}=2(d-1) d^{2}$. We conclude that $2(d-1)$ is 3 times a square. This is satisfied if $d-1=6 n^{2}$ for some $n$. Thus $d=6 n^{2}+1$ and $3 y^{2}=d^{2} \cdot 2\left(6 n^{2}\right)$ giving us $y^{2}=4 d^{2} n^{2}$. Thus we can take $y=2 d n=2 n\left(6 n^{2}+1\right)$. From this we obtain $x=y-d=(2 n-1)\left(6 n^{2}+1\right), z=y+d=(2 n+1)\left(6 n^{2}+1\right)$. It is easily verified that

|

| 50 |

+

|

| 51 |

+

$$

|

| 52 |

+

(x, y, z)=\left((2 n-1)\left(6 n^{2}+1\right), 2 n\left(6 n^{2}+1\right),(2 n+1)\left(6 n^{2}+1\right)\right)

|

| 53 |

+

$$

|

| 54 |

+

|

| 55 |

+

is indeed a solution for a fixed $n$ and this gives an infinite set of solutions as $n$ varies over natural numbers.

|

| 56 |

+

|

| 57 |

+

3. If $a, b, c$ are positive real numbers such that $a b c=1$, prove that

|

| 58 |

+

|

| 59 |

+

$$

|

| 60 |

+

a^{b+c} b^{c+a} c^{a+b} \leq 1

|

| 61 |

+

$$

|

| 62 |

+

|

| 63 |

+

Solution: Note that the inequality is symmetric in $a, b, c$ so that we may assume that $a \geq b \geq c$. Since $a b c=1$, it follows that $a \geq 1$ and $c \leq 1$. Using $b=1 / a c$, we get

|

| 64 |

+

|

| 65 |

+

$$

|

| 66 |

+

a^{b+c} b^{c+a} c^{a+b}=\frac{a^{b+c} c^{a+b}}{a^{c+a} c^{c+a}}=\frac{c^{b-c}}{a^{a-b}} \leq 1

|

| 67 |

+

$$

|

| 68 |

+

|

| 69 |

+

because $c \leq 1, b \geq c, a \geq 1$ and $a \geq b$.

|

| 70 |

+

|

| 71 |

+

4. Given any nine integers show that it is possible to choose, from among them, four integers $a, b, c, d$ such that $a+b-c-d$ is divisible by 20 . Further show that such a selection is not possible if we start with eight integers instead of nine.

|

| 72 |

+

|

| 73 |

+

## Solution:

|

| 74 |

+

|

| 75 |

+

Suppose there are four numbers $a, b, c, d$ among the given nine numbers which leave the same remainder modulo 20 . Then $a+b \equiv c+d(\bmod 20)$ and we are done.

|

| 76 |

+

|

| 77 |

+

If not, there are two possibilities:

|

| 78 |

+

|

| 79 |

+

(1) We may have two disjoint pairs $\{a, c\}$ and $\{b, d\}$ obtained from the given nine numbers such that $a \equiv c(\bmod 20)$ and $b \equiv d(\bmod 20)$. In this case we get $a+b \equiv c+d$ $(\bmod 20)$.

|

| 80 |

+

|

| 81 |

+

(2) Or else there are at most three numbers having the same remainder modulo 20 and the remaining six numbers leave distinct remainders which are also different from the first remainder (i.e., the remainder of the three numbers). Thus there are at least 7 disinct remainders modulo 20 that can be obtained from the given set of nine numbers. These 7 remainders give rise to $\binom{7}{2}=21$ pairs of numbers. By pigeonhole principle, there must be two pairs $\left(r_{1}, r_{2}\right),\left(r_{3}, r_{4}\right)$ such that $r_{1}+r_{2} \equiv r_{3}+r_{4}(\bmod 20)$. Going back we get four numbers $a, b, c, d$ such that $a+b \equiv c+d(\bmod 20)$.

|

| 82 |

+

|

| 83 |

+

If we take the numbers $0,0,0,1,2,4,7,12$, we check that the result is not true for these eight numbers.

|

| 84 |

+

|

| 85 |

+

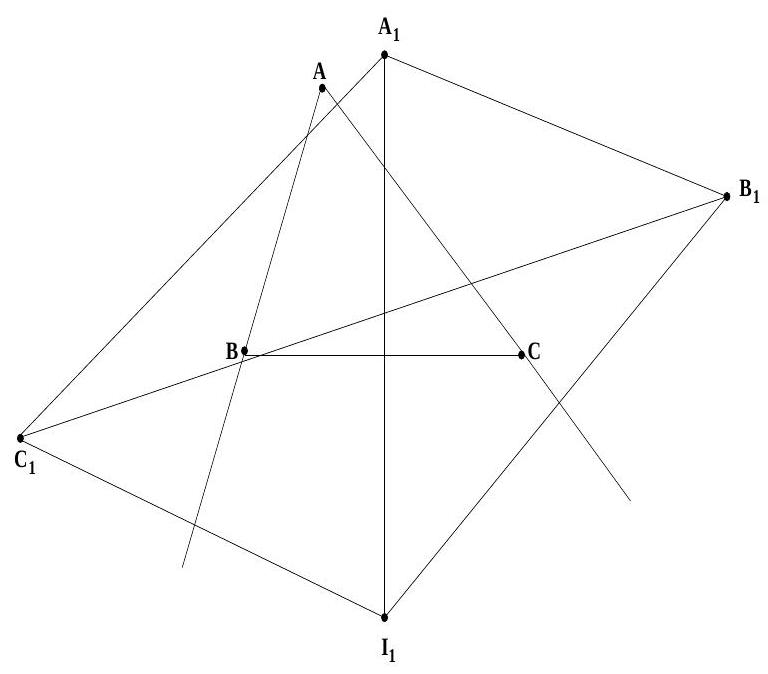

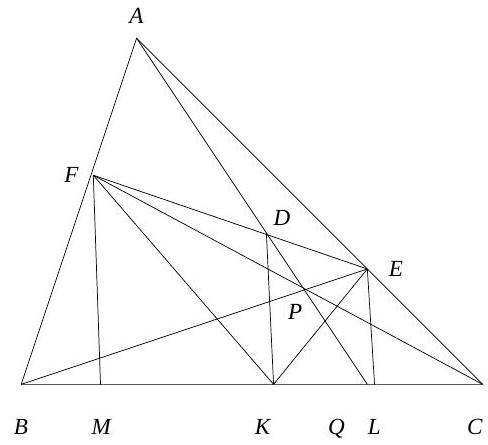

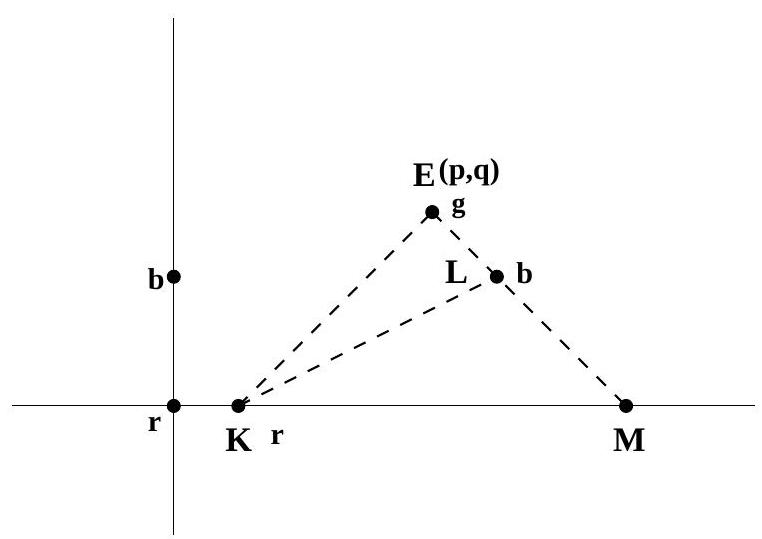

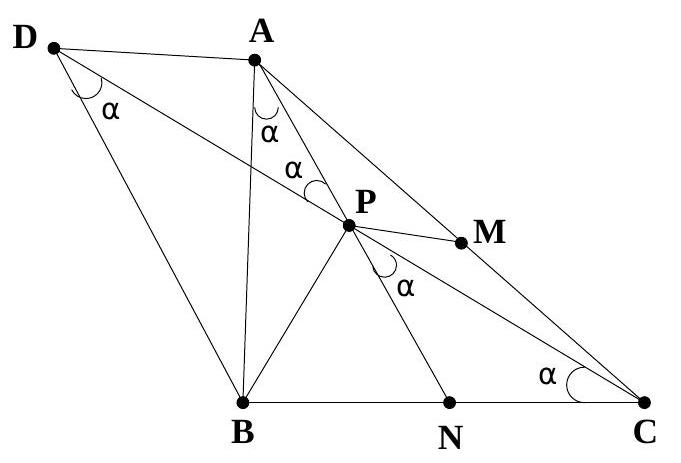

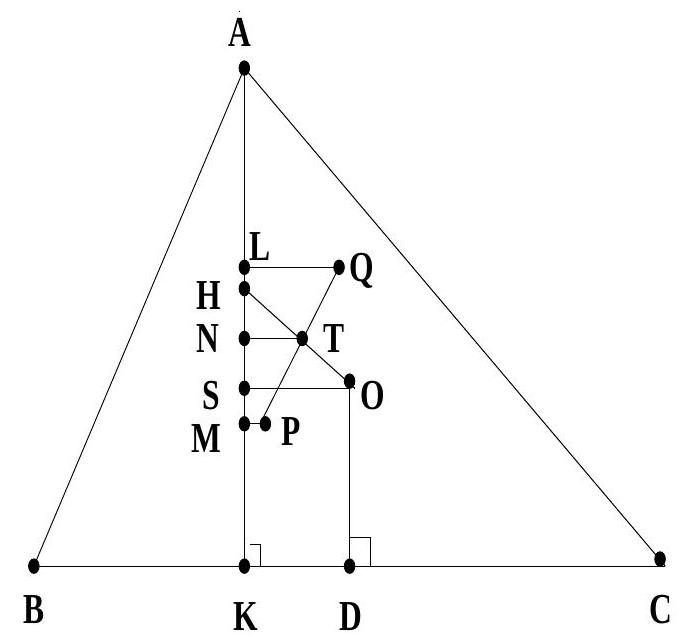

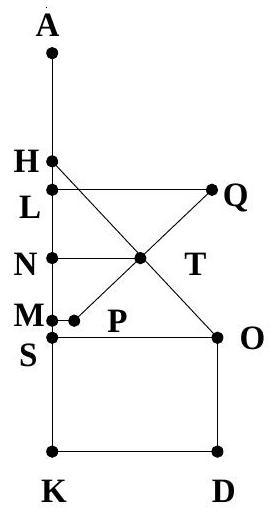

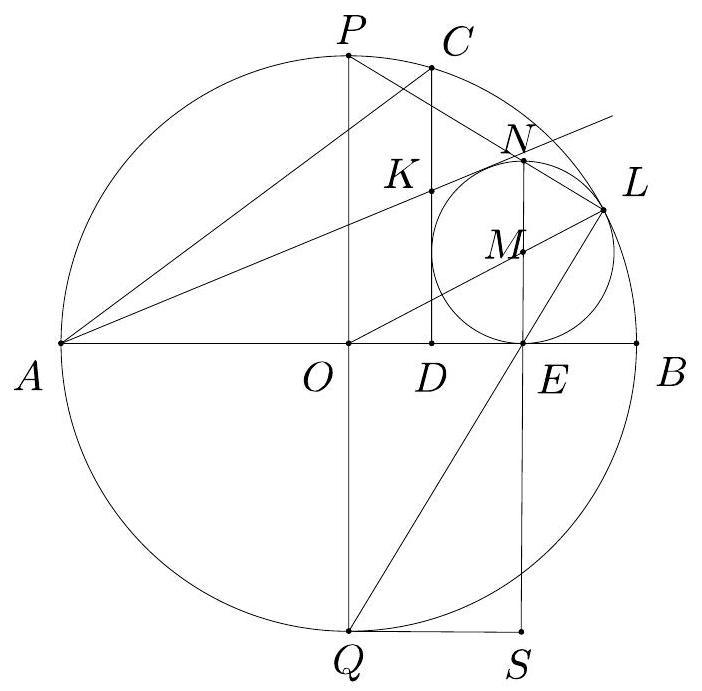

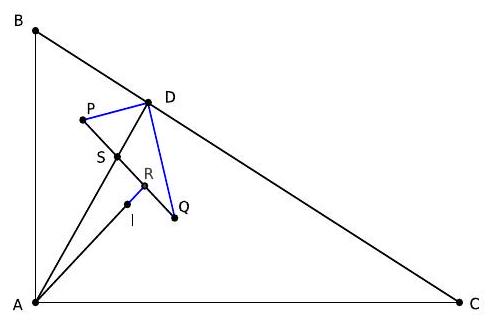

5. Let $A B C$ be a triangle and $D$ be the mid-point of side $B C$. Suppose $\angle D A B=\angle B C A$ and $\angle D A C=15^{\circ}$. Show that $\angle A D C$ is obtuse. Further, if $O$ is the circumcentre of $A D C$, prove that triangle $A O D$ is equilateral.

|

| 86 |

+

|

| 87 |

+

## Solution:

|

| 88 |

+

|

| 89 |

+

|

| 90 |

+

|

| 91 |

+

Let $\alpha$ denote the equal angles $\angle B A D=\angle D C A$. Using sine rule in triangles $D A B$ and $D A C$, we get

|

| 92 |

+

|

| 93 |

+

$$

|

| 94 |

+

\frac{A D}{\sin B}=\frac{B D}{\sin \alpha}, \quad \frac{C D}{\sin 15^{\circ}}=\frac{A D}{\sin \alpha}

|

| 95 |

+

$$

|

| 96 |

+

|

| 97 |

+

Eliminating $\alpha$ (using $B D=D C$ and $2 \alpha+B+15^{\circ}=\pi$ ), we obtain $1+\cos \left(B+15^{\circ}\right)=$ $2 \sin B \sin 15^{\circ}$. But we know that $2 \sin B \sin 15^{\circ}=\cos \left(B-15^{\circ}\right)-\cos \left(B+15^{\circ}\right)$. Putting $\beta=B-15^{\circ}$, we get a relation $1+2 \cos (\beta+30)=\cos \beta$. We write this in the form

|

| 98 |

+

|

| 99 |

+

$$

|

| 100 |

+

(1-\sqrt{3}) \cos \beta+\sin \beta=1

|

| 101 |

+

$$

|

| 102 |

+

|

| 103 |

+

Since $\sin \beta \leq 1$, it follows that $(1-\sqrt{3}) \cos \beta \geq 0$. We conclude that $\cos \beta \leq 0$ and hence that $\beta$ is obtuse. So is angle $B$ and hence $\angle A D C$.

|

| 104 |

+

|

| 105 |

+

We have the relation $(1-\sqrt{3}) \cos \beta+\sin \beta=1$. If we set $x=\tan (\beta / 2)$, then we get, using $\cos \beta=\left(1-x^{2}\right) /\left(1+x^{2}\right), \sin \beta=2 x /\left(1+x^{2}\right)$,

|

| 106 |

+

|

| 107 |

+

$$

|

| 108 |

+

(\sqrt{3}-2) x^{2}+2 x-\sqrt{3}=0

|

| 109 |

+

$$

|

| 110 |

+

|

| 111 |

+

Solving for $x$, we obtain $x=1$ or $x=\sqrt{3}(2+\sqrt{3})$. If $x=\sqrt{3}(2+\sqrt{3})$, then $\tan (\beta / 2)>2+\sqrt{3}=\tan 75^{\circ}$ giving us $\beta>150^{\circ}$. This forces that $B>165^{\circ}$ and hence $B+A>165^{\circ}+15^{\circ}=180^{\circ}$, a contradiction. thus $x=1$ giving us $\beta=\pi / 2$. This gives $B=105^{\circ}$ and hence $\alpha=30^{\circ}$. Thus $\angle D A O=60^{\circ}$. Since $O A=O D$, the result follows.

|

| 112 |

+

|

| 113 |

+

## OR

|

| 114 |

+

|

| 115 |

+

Let $m_{a}$ denote the median $A D$. Then we can compute

|

| 116 |

+

|

| 117 |

+

$$

|

| 118 |

+

\cos \alpha=\frac{c^{2}+m_{a}^{2}-\left(a^{2} / 4\right)}{2 c m_{a}}, \quad \sin \alpha=\frac{2 \Delta}{c m_{a}}

|

| 119 |

+

$$

|

| 120 |

+

|

| 121 |

+

where $\Delta$ denotes the area of triangle $A B C$. These two expressions give

|

| 122 |

+

|

| 123 |

+

$$

|

| 124 |

+

\cot \alpha=\frac{c^{2}+m_{a}^{2}-\left(a^{2} / 4\right)}{4 \Delta}

|

| 125 |

+

$$

|

| 126 |

+

|

| 127 |

+

Similarly, we obtain

|

| 128 |

+

|

| 129 |

+

$$

|

| 130 |

+

\cot \angle C A D=\frac{b^{2}+m_{a}^{2}-\left(a^{2} / 4\right)}{4 \Delta}

|

| 131 |

+

$$

|

| 132 |

+

|

| 133 |

+

Thus we get

|

| 134 |

+

|

| 135 |

+

$$

|

| 136 |

+

\cot \alpha-\cot 15^{\circ}=\frac{c^{2}-a^{2}}{4 \Delta}

|

| 137 |

+

$$

|

| 138 |

+

|

| 139 |

+

Similarly we can also obtain

|

| 140 |

+

|

| 141 |

+

$$

|

| 142 |

+

\cot B-\cot \alpha=\frac{c^{2}-a^{2}}{4 \Delta}

|

| 143 |

+

$$

|

| 144 |

+

|

| 145 |

+

giving us the relation

|

| 146 |

+

|

| 147 |

+

$$

|

| 148 |

+

\cot B=2 \cot \alpha-\cot 15^{\circ}

|

| 149 |

+

$$

|

| 150 |

+

|

| 151 |

+

If $B$ is acute then $2 \cot \alpha>\cot 15^{\circ}=2+\sqrt{3}>2 \sqrt{3}$. It follows that $\cot \alpha>\sqrt{3}$. This implies that $\alpha<30^{\circ}$ and hence

|

| 152 |

+

|

| 153 |

+

$$

|

| 154 |

+

B=180^{\circ}-2 \alpha-15^{\circ}>105^{\circ}

|

| 155 |

+

$$

|

| 156 |

+

|

| 157 |

+

This contradiction forces that angle $B$ is obtuse and consequently $\angle A D C$ is obtuse.

|

| 158 |

+

|

| 159 |

+

Since $\angle B A D=\alpha=\angle A C D$, the line $A B$ is tangent to the circumcircle $\Gamma$ of $A D C$ at $A$. Hence $O A$ is perpendicular to $A B$. Draw $D E$ and $B F$ perpendicular to $A C$, and join $O D$. Since $\angle D A C=15^{\circ}$, we see that $\angle D O C=30^{\circ}$ and hence $D E=O D / 2$. But $D E$ is parallel to $B F$ and $B D=D C$ shows that $B F=2 D E$. We conclude that

|

| 160 |

+

$B F=D O$. But $D O=A O$, both being radii of $\Gamma$. Thus $B F=A O$. Using right triangles $B F O$ and $B A O$, we infer that $A B=O F$. We conclude that $A B F O$ is a rectangle. In particular $\angle A O F=90^{\circ}$. It follows that

|

| 161 |

+

|

| 162 |

+

$$

|

| 163 |

+

\angle A O D=90^{\circ}-\angle D O C=90^{\circ}-30^{\circ}=60^{\circ}

|

| 164 |

+

$$

|

| 165 |

+

|

| 166 |

+

Since $O A=O D$, we conclude that $A O D$ is equilateral.

|

| 167 |

+

|

| 168 |

+

OR

|

| 169 |

+

|

| 170 |

+

Note that triangles $A B D$ and $C B A$ are similar. Thus we have the ratios

|

| 171 |

+

|

| 172 |

+

$$

|

| 173 |

+

\frac{A B}{B D}=\frac{C B}{B A}

|

| 174 |

+

$$

|

| 175 |

+

|

| 176 |

+

This reduces to $a^{2}=2 c^{2}$ giving us $a=\sqrt{2} c$. This is equivalent to $\sin ^{2}\left(\alpha+15^{\circ}\right)=$ $2 \sin ^{2} \alpha$. We write this in the form

|

| 177 |

+

|

| 178 |

+

$$

|

| 179 |

+

\cos 15^{\circ}+\cot \alpha \sin 15^{\circ}=\sqrt{2}

|

| 180 |

+

$$

|

| 181 |

+

|

| 182 |

+

Solving for $\cot \alpha$, we get $\cot \alpha=\sqrt{3}$. We conclude that $\alpha=30^{\circ}$, and the result follows.

|

| 183 |

+

|

| 184 |

+

6. Let $\mathbf{R}$ denote the set of all real numbers. Find all functions $f: \mathbf{R} \rightarrow \mathbf{R}$ satisfying the condition

|

| 185 |

+

|

| 186 |

+

$$

|

| 187 |

+

f(x+y)=f(x) f(y) f(x y)

|

| 188 |

+

$$

|

| 189 |

+

|

| 190 |

+

for all $x, y$ in $\mathbf{R}$.

|

| 191 |

+

|

| 192 |

+

Solution: Putting $x=0, y=0$, we get $f(0)=f(0)^{3}$ so that $f(0)=0,1$ or -1 . If $f(0)=0$, then taking $y=0$ in the given equation, we obtain $f(x)=f(x) f(0)^{2}=0$ for all $x$.

|

| 193 |

+

|

| 194 |

+

Suppose $f(0)=1$. Taking $y=-x$, we obtain

|

| 195 |

+

|

| 196 |

+

$$

|

| 197 |

+

1=f(0)=f(x-x)=f(x) f(-x) f\left(-x^{2}\right)

|

| 198 |

+

$$

|

| 199 |

+

|

| 200 |

+

This shows that $f(x) \neq 0$ for any $x \in \mathbf{R}$. Taking $x=1, y=x-1$, we obtain

|

| 201 |

+

|

| 202 |

+

$$

|

| 203 |

+

f(x)=f(1) f(x-1)^{2}=f(1)[f(x) f(-x) f(-x)]^{2}

|

| 204 |

+

$$

|

| 205 |

+

|

| 206 |

+

Using $f(x) \neq 0$, we conclude that $1=k f(x)(f(-x))^{2}$, where $k=$

|

| 207 |

+

|

| 208 |

+

$f(1)(f(-1))^{2}$. Changing $x$ to $-x$ here, we also infer that $1=k f(-x)(f(x))^{2}$. Comparing these expressions we see that $f(-x)=f(x)$. It follows that $1=k f(x)^{3}$. Thus $f(x)$ is constant for all $x$. Since $f(0)=1$, we conclude that $f(x)=1$ for all real $x$.

|

| 209 |

+

|

| 210 |

+

If $f(0)=-1$, a similar analysis shows that $f(x)=-1$ for all $x \in \mathbf{R}$. We can verify that each of these functions satisfies the given functional equation. Thus there are three solutions, all of them being constant functions.

|

| 211 |

+

|

INMO/md/en-2002.md

ADDED

|

@@ -0,0 +1,196 @@

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 1 |

+

# Solution to INMO-2002 Problems

|

| 2 |

+

|

| 3 |

+

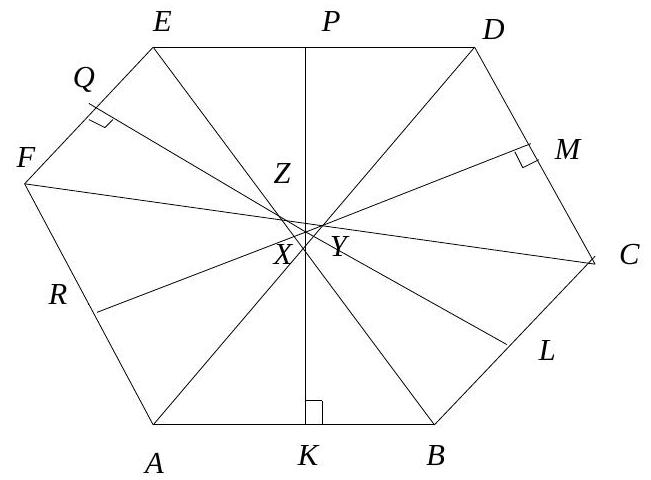

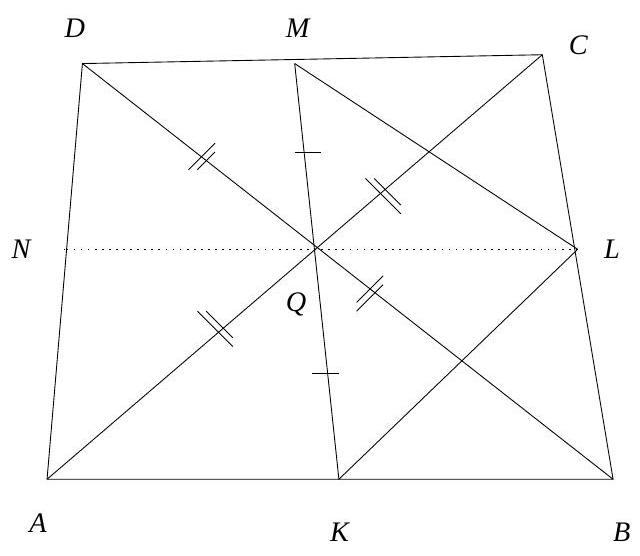

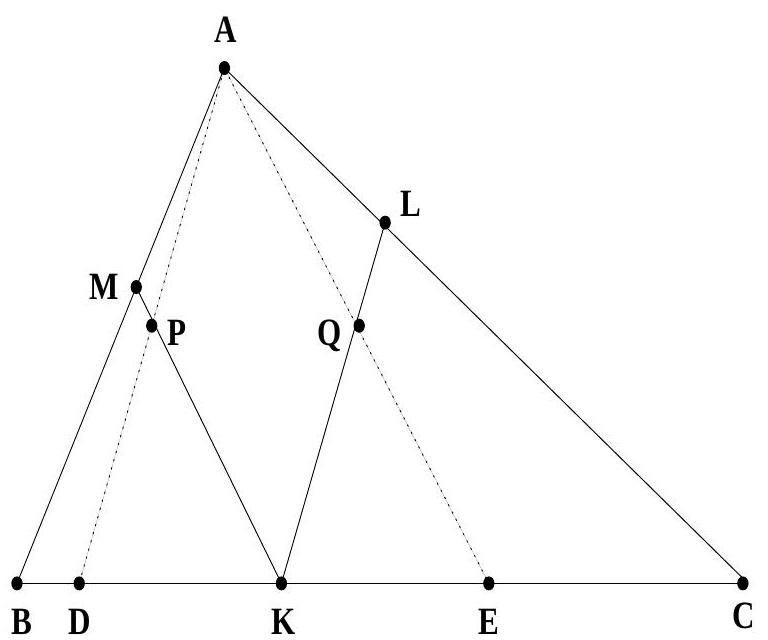

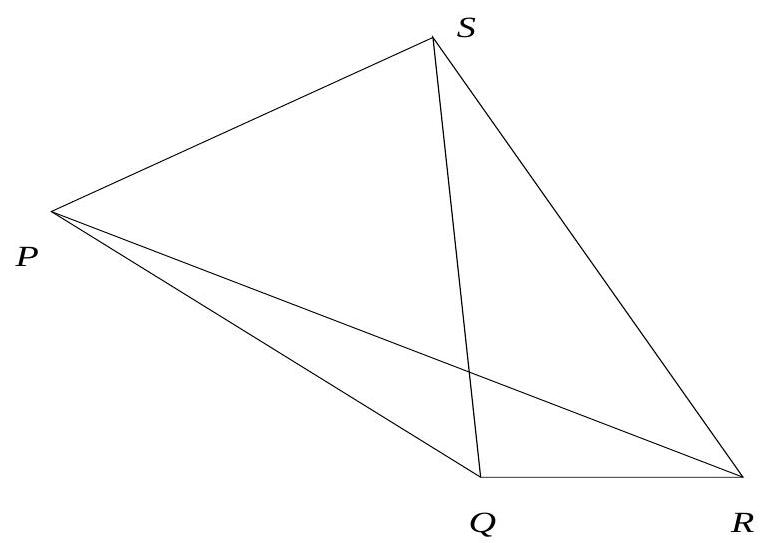

1. For a convex hexagon $A B C D E F$ in which each pair of opposite sides is unequal, consider the following six statements:

|

| 4 |

+

|

| 5 |

+

$$

|

| 6 |

+

\begin{array}{ll}

|

| 7 |

+

\text { (a } \left.\mathrm{a}_{1}\right) A B \text { is parallel to } D E ; & \left(\mathrm{a}_{2}\right) A E=B D \\

|

| 8 |

+

\left(\mathrm{~b}_{1}\right) B C \text { is parallel to } E F ; & \left(\mathrm{b}_{2}\right) B F=C E \\

|

| 9 |

+

\text { (c } \left.\mathrm{c}_{1}\right) C D \text { is parallel to } F A ; & \left(\mathrm{c}_{2}\right) C A=D F

|

| 10 |

+

\end{array}

|

| 11 |

+

$$

|

| 12 |

+

|

| 13 |

+

(a) Show that if all the six statements are true, then the hexagon is cyclic(i.e., it can be inscribed in a circle).

|

| 14 |

+

|

| 15 |

+

(b) Prove that, in fact, any five of these six statements also imply that the hexagon is cyclic.

|

| 16 |

+

|

| 17 |

+

## Solution:

|

| 18 |

+

|

| 19 |

+

(a) Suppose all the six statements are true. Then $A B D E, B C E F, C D F A$ are isosceles trapeziums; if $K, L, M, P, Q, R$ are the mid-points of $A B, B C$, $C D, D E, E F, F A$ respectively, then we see that $K P \perp A B, E D ; L Q \perp$ $B C, E F$ and $M R \perp C D, F A$.

|

| 20 |

+

|

| 21 |

+

|

| 22 |

+

|

| 23 |

+

If $A D, B E, C F$ themselves concur at a point $O$, then $O A=O B=O C=$ $O D=O E=O F$. ( $O$ is on the perpendicular bisector of each of the sides.) Hence $A, B, C, D, E, F$ are concyclic and lie on a circle with centre $O$. Otherwise these lines $A D, B E, C F$ form a triangle, say $X Y Z$. (See Fig.) Then $K X, M Y, Q Z$, when extended, become the internal angle bisectors of the triangle $X Y Z$ and hence concur at the incentre $O^{\prime}$ of $X Y Z$. As earlier $O^{\prime}$ lies on the perpendicular bisector of each of the sides. Hence $O^{\prime} A=O^{\prime} B$ $=O^{\prime} C=O^{\prime} D=O^{\prime} E=O^{\prime} F$, giving the concyclicity of $A, B, C, D, E, F$.

|

| 24 |

+

(b) Suppose $\left(\mathrm{a}_{1}\right),\left(\mathrm{a}_{2}\right),\left(\mathrm{b}_{1}\right),\left(\mathrm{b}_{2}\right)$ are true. Then we see that $A D=B E=$ $C F$. Assume that ( $\mathrm{c}_{1}$ ) is true. Then $C D$ is parallel to $A F$. It follows that triangles $Y C D$ and $Y F A$ are similar. This gives

|

| 25 |

+

|

| 26 |

+

$$

|

| 27 |

+

\frac{F Y}{A Y}=\frac{Y C}{Y D}=\frac{F Y+Y C}{A Y+Y D}=\frac{F C}{A D}=1

|

| 28 |

+

$$

|

| 29 |

+

|

| 30 |

+

We obtain $F Y=A Y$ and $Y C=Y D$. This forces that triangles $C Y A$ and $D Y F$ are congruent. In particular $A C=D F$ so that ( $\mathrm{c}_{2}$ ) is true. The conclusion follows from (a). Now assume that ( $\mathrm{c}_{2}$ ) is true; i.e., $A C=F D$. We have seen that $A D=B E=C F$. It follows that triangles $F D C$ and $A C D$ are congruent. In particular $\angle A D C=\angle F C D$. Similarly, we can show that $\angle C F A=\angle D A F$. We conclude that $C D$ is parallel to $A F$ giving $\left(\mathrm{c}_{1}\right.$ ).

|

| 31 |

+

|

| 32 |

+

2. Determine the least positive value taken by the expression $a^{3}+b^{3}+c^{3}-3 a b c$ as $a, b, c$ vary over all positive integers. Find also all triples $(a, b, c)$ for which this least value is attained.

|

| 33 |

+

|

| 34 |

+

Solution: We observe that

|

| 35 |

+

|

| 36 |

+

$$

|

| 37 |

+

\left.Q=a^{3}+b^{3}+c^{3}-3 a b c=\frac{1}{2}(a+b+c)\right)\left((a-b)^{2}+(b-c)^{2}+(c-a)^{2}\right)

|

| 38 |

+

$$

|

| 39 |

+

|

| 40 |

+

Since we are looking for the least positive value taken by $Q$, it follows that $a, b, c$ are not all equal. Thus $a+b+c \geq 1+1+2=4$ and $(a-b)^{2}+(b-$ $c)^{2}+(c-a)^{2} \geq 1+1+0=2$. Thus we see that $Q \geq 4$. Taking $a=1$, $b=1$ and $c=2$, we get $Q=4$. Therefore the least value of $Q$ is 4 and this is achieved only by $a+b+c=4$ and $(a-b)^{2}+(b-c)^{2}+(c-a)^{2}=2$. The triples for which $Q=4$ are therefore given by

|

| 41 |

+

|

| 42 |

+

$$

|

| 43 |

+

(a, b, c)=(1,1,2),(1,2,1),(2,1,1)

|

| 44 |

+

$$

|

| 45 |

+

|

| 46 |

+

3. Let $x, y$ be positive reals such that $x+y=2$. Prove that

|

| 47 |

+

|

| 48 |

+

$$

|

| 49 |

+

x^{3} y^{3}\left(x^{3}+y^{3}\right) \leq 2

|

| 50 |

+

$$

|

| 51 |

+

|

| 52 |

+

Solution: We have from the AM-GM inequality, that

|

| 53 |

+

|

| 54 |

+

$$

|

| 55 |

+

x y \leq\left(\frac{x+y}{2}\right)^{2}=1

|

| 56 |

+

$$

|

| 57 |

+

|

| 58 |

+

Thus we obtain $0<x y \leq 1$. We write

|

| 59 |

+

|

| 60 |

+

$$

|

| 61 |

+

\begin{aligned}

|

| 62 |

+

x^{3} y^{3}\left(x^{3}+y^{3}\right) & =(x y)^{3}(x+y)\left(x^{2}-x y+y^{2}\right) \\

|

| 63 |

+

& =2(x y)^{3}\left((x+y)^{2}-3 x y\right) \\

|

| 64 |

+

& =2(x y)^{3}(4-3 x y)

|

| 65 |

+

\end{aligned}

|

| 66 |

+

$$

|

| 67 |

+

|

| 68 |

+

Thus we need to prove that

|

| 69 |

+

|

| 70 |

+

$$

|

| 71 |

+

(x y)^{3}(4-3 x y) \leq 1

|

| 72 |

+

$$

|

| 73 |

+

|

| 74 |

+

Putting $z=x y$, this inequality reduces to

|

| 75 |

+

|

| 76 |

+

$$

|

| 77 |

+

z^{3}(4-3 z) \leq 1

|

| 78 |

+

$$

|

| 79 |

+

|

| 80 |

+

for $0<z \leq 1$. We can prove this in different ways. We can put the inequality in the form

|

| 81 |

+

|

| 82 |

+

$$

|

| 83 |

+

3 z^{4}-4 z^{3}+1 \geq 0

|

| 84 |

+

$$

|

| 85 |

+

|

| 86 |

+

Here the expression in the LHS factors to $(z-1)^{2}\left(3 z^{2}+2 z+1\right)$ and $\left(3 z^{2}+2 z+1\right)$ is positive since its discriminant $D=-8<0$. Or applying the AM-GM inequality to the positive reals $4-3 z, z, z, z$, we obtain

|

| 87 |

+

|

| 88 |

+

$$

|

| 89 |

+

z^{3}(4-3 z) \leq\left(\frac{4-3 z+3 z}{4}\right)^{4} \leq 1

|

| 90 |

+

$$

|

| 91 |

+

|

| 92 |

+

4. Do there exist 100 lines in the plane, no three of them concurrent, such that they intersect exactly in 2002 points?

|

| 93 |

+

|

| 94 |

+

Solution: Any set of 100 lines in the plane can be partitioned into a finite number of disjoint sets, say $A_{1}, A_{2}, A_{3}, \ldots, A_{k}$, such that

|

| 95 |

+

|

| 96 |

+

(i) Any two lines in each $A_{j}$ are parallel to each other, for $1 \leq j \leq k$ (provided, of course, $\left|A_{j}\right| \geq 2$ );

|

| 97 |

+

|

| 98 |

+

(ii) for $j \neq l$, the lines in $A_{j}$ and $A_{l}$ are not parallel.

|

| 99 |

+

|

| 100 |

+

If $\left|A_{j}\right|=m_{j}, 1 \leq j \leq k$, then the total number of points of intersection is given by $\sum_{1 \leq j \leq l \leq k} m_{j} m_{l}$, as no three lines are concurrent. Thus we have to find positive integers $m_{1}, m_{2}, \ldots, m_{k}$ such that

|

| 101 |

+

|

| 102 |

+

$$

|

| 103 |

+

\sum_{j=1}^{k} m_{j}=100, \quad \sum m_{j} m_{l}=2002

|

| 104 |

+

$$

|

| 105 |

+

|

| 106 |

+

for an affirmative answer to the given question.

|

| 107 |

+

|

| 108 |

+

We observe that

|

| 109 |

+

|

| 110 |

+

$$

|

| 111 |

+

\begin{aligned}

|

| 112 |

+

\sum_{j=1}^{k} m_{j}^{2} & =\left(\sum_{j=1}^{k} m_{j}\right)^{2}-2\left(\sum m_{j} m_{l}\right) \\

|

| 113 |

+

& =100^{2}-2(2002)=5996

|

| 114 |

+

\end{aligned}

|

| 115 |

+

$$

|

| 116 |

+

|

| 117 |

+

Thus we have to choose $m_{1}, m_{2}, \ldots, m_{k}$ such that

|

| 118 |

+

|

| 119 |

+

$$

|

| 120 |

+

\sum_{j=1}^{k} m_{j}=100, \quad \sum_{j=1}^{k} m_{j}^{2}=5996

|

| 121 |

+

$$

|

| 122 |

+

|

| 123 |

+

We observe that $[\sqrt{5996}]=77$. So we may take $m_{1}=77$, so that

|

| 124 |

+

|

| 125 |

+

$$

|

| 126 |

+

\sum_{j=2}^{k} m_{j}=23, \quad \sum j=2^{k} m_{j}^{2}=67

|

| 127 |

+

$$

|

| 128 |

+

|

| 129 |

+

Now we may choose $m_{2}=5, m_{3}=m_{4}=4, m_{5}=m_{6}=\cdots=m_{14}=1$. Finally, we can take

|

| 130 |

+

|

| 131 |

+

$$

|

| 132 |

+

k=14, \quad\left(m_{1}, m_{2}, \ldots, m_{14}\right)=(77,5,4,4,1,1,1,1,1,1,1,1,1,1)

|

| 133 |

+

$$

|

| 134 |

+

|

| 135 |

+

proving the existence of 100 lines with exactly 2002 points of intersection.

|

| 136 |

+

|

| 137 |

+

5. Do there exist three distinct positive real numbers $a, b, c$ such that the numbers $a, b, c, b+c-a, c+a-b, a+b-c$ and $a+b+c$ form a 7-term arithmetic progression in some order?

|

| 138 |

+

|

| 139 |

+

Solution: We show that the answer is NO. Suppose, if possible, let $a, b, c$ be three distinct positive real numbers such that $a, b, c, b+c-a, c+a-b$, $a+b-c$ and $a+b+c$ form a 7-term arithmetic progression in some order. We may assume that $a<b<c$. Then there are only two cases we need to check: (I) $a+b-c<a<c+a-b<b<c<b+c-a<a+b+c$ and (II) $a+b-c<a<b<c+a-b<c<b+c-a<a+b+c$.

|

| 140 |

+

|

| 141 |

+

Case I. Suppose the chain of inequalities $a+b-c<a<c+a-b<b<$ $c<b+c-a<a+b+c$ holds good. let $d$ be the common difference. Thus we see that

|

| 142 |

+

|

| 143 |

+

$$

|

| 144 |

+

c=a+b+c-2 d, b=a+b+c-3 d, a=a+b+c-5 d

|

| 145 |

+

$$

|

| 146 |

+

|

| 147 |

+

Adding these, we see that $a+b+c=5 d$. But then $a=0$ contradicting the positivity of $a$.

|

| 148 |

+

|

| 149 |

+

Case II. Suppose the inequalities $a+b-c<a<b<c+a-b<c<$ $b+c-a<a+b+c$ are true. Again we see that

|

| 150 |

+

|

| 151 |

+

$$

|

| 152 |

+

c=a+b+c-2 d, b=a+b+c-4 d, a=a+b+c-5 d

|

| 153 |

+

$$

|

| 154 |

+

|

| 155 |

+

We thus obtain $a+b+c=(11 / 2) d$. This gives

|

| 156 |

+

|

| 157 |

+

$$

|

| 158 |

+

a=\frac{1}{2} d, b=\frac{3}{2} d, c=\frac{7}{2} d

|

| 159 |

+

$$

|

| 160 |

+

|

| 161 |

+

Note that $a+b-c=a+b+c-6 d=-(1 / 2) d$. However we also get $a+b-c=[(1 / 2)+(3 / 2)-(7 / 2)] d=-(3 / 2) d$. It follows that $3 e=e$ giving $d=0$. But this is impossible.

|

| 162 |

+

|

| 163 |

+

Thus there are no three distinct positive real numbers $a, b, c$ such that $a$, $b, c, b+c-a, c+a-b, a+b-c$ and $a+b+c$ form a 7-term arithmetic progression in some order.

|

| 164 |

+

|

| 165 |

+

6. Suppose the $n^{2}$ numbers $1,2,3, \ldots, n^{2}$ are arranged to form an $n$ by $n$ array consisting of $n$ rows and $n$ columns such that the numbers in each row(from left to right) and each column(from top to bottom) are in increasing order. Denote by $a_{j k}$ the number in $j$-th row and $k$-th column. Suppose $b_{j}$ is the maximum possible number of entries that can occur as $a_{j j}, 1 \leq j \leq n$. Prove that

|

| 166 |

+

|

| 167 |

+

$$

|

| 168 |

+

b_{1}+b_{2}+b_{3}+\cdots b_{n} \leq \frac{n}{3}\left(n^{2}-3 n+5\right)

|

| 169 |

+

$$

|

| 170 |

+

|

| 171 |

+

(Example: In the case $n=3$, the only numbers which can occur as $a_{22}$ are 4,5 or 6 so that $b_{2}=3$.)

|

| 172 |

+

|

| 173 |

+

Solution: Since $a_{j j}$ has to exceed all the numbers in the top left $j \times j$ submatrix (excluding itself), and since there are $j^{2}-1$ entries, we must have $a_{j j} \geq j^{2}$. Similarly, $a_{j j}$ must not exceed eac of the numbers in the bottom right $(n-j+1) \times(n-j+1)$ submatrix (other than itself) and there are $(n-j+1)^{2}-1$ such entries giving $a_{j j} \leq n^{2}-(n-j+1)^{2}+1$. Thus we see that

|

| 174 |

+

|

| 175 |

+

$$

|

| 176 |

+

a_{j j} \in\left\{j^{2}, j^{2}+1, j^{2}+2, \ldots, n^{2}-(n-j+1)^{2}+1\right\}

|

| 177 |

+

$$

|

| 178 |

+

|

| 179 |

+

The number of elements in this set is $n^{2}-(n-j+1)^{2}-j^{2}+2$. This implies that

|

| 180 |

+

|

| 181 |

+

$$

|

| 182 |

+

b_{j} \leq n^{2}-(n-j+1)^{2}-j^{2}+2=(2 n+2) j-2 j^{2}-(2 n-1)

|

| 183 |

+

$$

|

| 184 |

+

|

| 185 |

+

It follows that

|

| 186 |

+

|

| 187 |

+

$$

|

| 188 |

+

\begin{aligned}

|

| 189 |

+

\sum_{j=1}^{n} b_{j} & \leq(2 n+2) \sum_{j=1}^{n} j-2 \sum_{j=1}^{n} j^{2}-n(2 n-1) \\

|

| 190 |

+

& =(2 n+2)\left(\frac{n(n+1)}{2}\right)-2\left(\frac{n(n+1)(2 n+1)}{6}\right)-n(2 n-1) \\

|

| 191 |

+

& =\frac{n}{3}\left(n^{2}-3 n+5\right)

|

| 192 |

+

\end{aligned}

|

| 193 |

+

$$

|

| 194 |

+

|

| 195 |

+

which is the required bound.

|

| 196 |

+

|

INMO/md/en-2003.md

ADDED

|

@@ -0,0 +1,194 @@

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 1 |

+

# Solutions to INMO-2003 problems

|

| 2 |

+

|

| 3 |

+